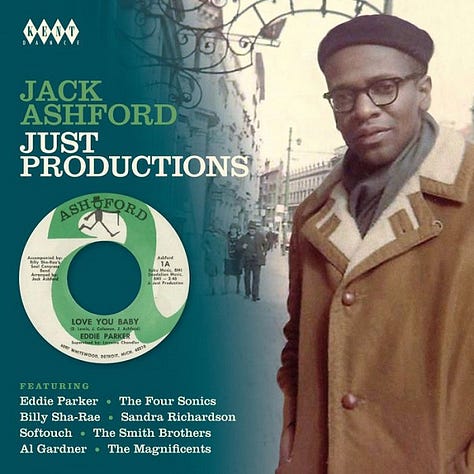

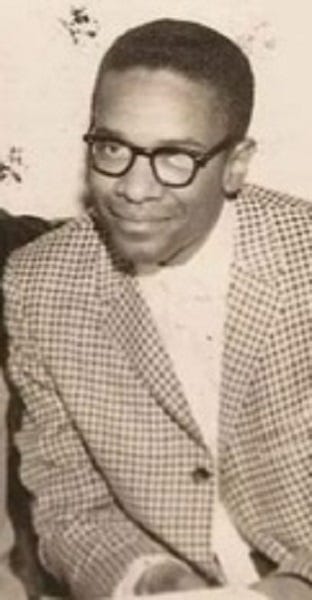

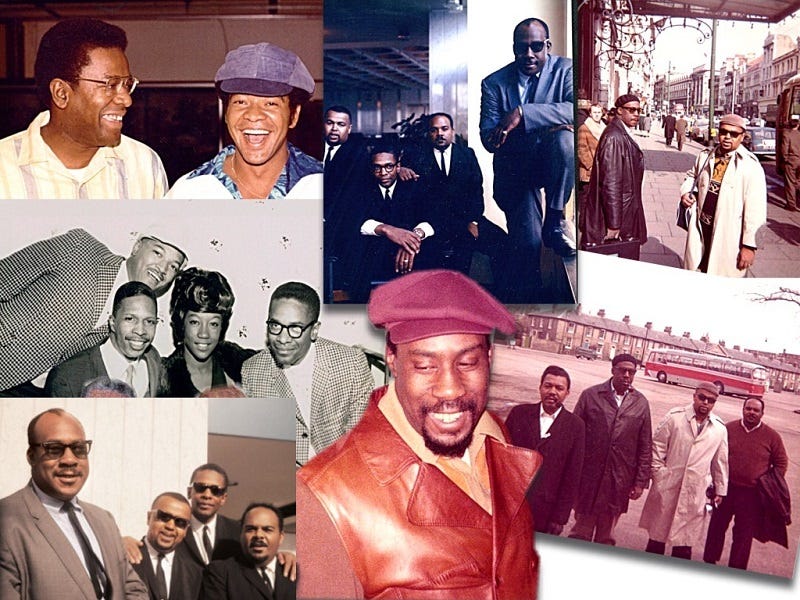

Exclusive Interview with Jack Ashford of Motown's Funk Brothers (born May 18, 1934)

The iconic percussionist who played on hundreds of Motown hits and is one of the greatest songwriters and producers of all time looks back over his career.

Jack Ashford is a legendary singer/songwriter, producer, composer, arranger, multi-instrumentalist, and label owner, and the last surviving original member of Motown's backing band the Funk Brothers. His contributions to the soundtrack of the past six decades have been immense.

Born in Philadelphia, Ashford started out as a vibe player before being hired by Motown in 1963 on the strength of his percussion skills. He initially played tambourine but later the entire catalog of percussive instruments. He was in high demand as a session musician and worked constantly. Ashford played on thousands of songs released by the label during the sixties and seventies, including nearly all of its top hits. He created a unique rhythm with the style of his tambourine playing that in turn helped shape the Motown sound.

Some of Ashford’s especially notable appearances include on “Nowhere To Run” by Martha and the Vandellas, Edwin Starr’s “War,” “I Heard It Through the Grapevine” by Marvin Gaye, and Thelma Houston’s “Don't Leave Me This Way.”

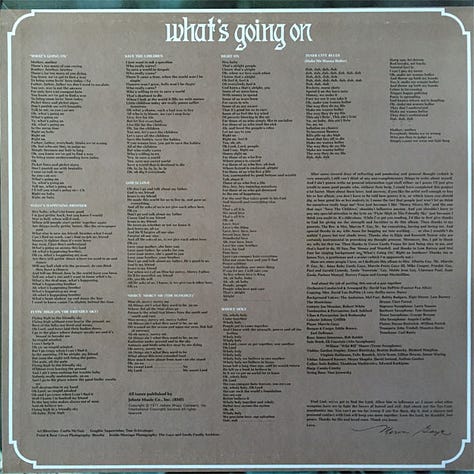

He is a skilled vibraphonist, and played the vibes on Gaye’s iconic hit “What’s Going On,” widely acknowledged as one of the top-five songs in history.

In addition to Ashford’s work at Motown, he is also one of the greatest unsung songwriters and producers of his generation, and arguably of all time. He founded his own independent production companies and record labels, and released a lengthy catalog of stellar records that many feel took the Motown sound to a higher level. Original copies of the records he wrote and produced routinely sell for hundreds or thousands of dollars today.

For the complete story of Ashford’s storied career at Motown and beyond, see his excellent 2003 autobiography Motown: The View from the Bottom which he wrote with his wife Charlene Ashford. See our earlier posts on his fellow original Funk Brother Robert White, singer Sandra Richardson who he wrote for and produced on his own labels, and Ashford’s songwriting and production partner Lorraine Chandler for more on his musical history.

To mark his 90th birthday, Ashford gave an exclusive, career retrospective interview to Jointz Of The Day, conducted and edited by DJ Dyn-O-Mite.

Click the links for most individual songs in this post to stream/purchase on your choice of platforms. Or open the YouTube playlist of all songs.

What an honor to talk with you so close to a milestone birthday like this. I guess we could say you’re almost officially a living legend.

I hear that! (Laughing)

Before Motown, what were some of your earliest touring gigs?

The Filippi brothers had a nightclub in Providence, Rhode Island (the Celebrity Club). They had a club there since 1950-something. We had fun going there. I was working with a band out of Philadelphia. In fact, that was the first band I ever worked with.

About how old were you?

Oh…19.

What was that band called?

The Hamiltones. The guy’s name was Carl Bell. He was the leader of the group. He was the drummer.

Were you playing percussion or vibes at that point?

I was only playing vibes. I didn’t stop playing vibes, well, officially, until I got to Motown. (At that point), I had never held a tambourine before.

Before we go any further, I just listened to the song “Shar” (1977) you wrote for (your wife) Charlene on your debut solo album, today for the very first time ever, and I just want to let you know, that is a phenomenal song!

I recorded that song at Marvin Gaye’s studio. Right up in Hollywood.

That’s outstanding.

Marvin took me to Motown, you know. He ran into me…history records that Marvin met me in Boston. I think it was Boston, but it was right on the route to Providence. Harvey Fuqua, his brother-in-law, who was with the Moonglows, they came in and heard me playing tambourine. That was the first time I’d ever played it, on that gig.

Was this with the original band you had started with?

No, it was with another band. I was with the Charles Harris Organ Trio then. And that’s when they walked in and heard…people were talking about this guy playing “jazz tambourine.” I didn’t want to play no tambourine, because I’d always associated it with the church. So I said, “Well, I don’t know anything about it.” And (I was told) “You gonna have to get ‘bout it now!” So I said, “Okay, it’s like that.” And the first song I played on it was “Take Five.”

By Dave Brubeck.

Absolutely. And I was amazed. When I touched it, it was like magic. In fact, the rest of the band was looking at me like, “(you) said you can’t play it, listen to this!” And the club has half-empty, (but) by the time we closed that night, it was like a row of clubs along this area where we were…but (people) were going up and down talking ‘bout, “There’s a guy playing jazz tambourine!” So now that I look back, that would be something to see! (Laughing)

Everybody came to the spot where you guys were.

That night, it created a little stir that night. It created a stir for me, because I’d never played it. The rhythm of “Take Five” was perfect for the tambourine. For what I do. Not for a regular 2/4 thing with the church. But for what I do, it fit perfectly.

I’ve always thought that was a pretty funky song.

Yeah! Absolutely, it certainly was.

So Marvin figured you’d be good to have in his touring band?

No…I did everything you could possibly do to not get the gig.

(Laughing)

The first night, when Harvey came in, he asked me would I mind if he brought his brother-in-law there to meet me. He said, “Because he’s forming a band.” He said, “You ever hear of Marvin Gaye?” I said, “No…what’s he play?” (Laughing) I was playing strictly jazz, you know. And so I knew nothing about Motown, none of those people. So I said, “Yeah, bring him in. That’s cool.” Another body in this building. So next night, when Marvin got there, it was packed. ‘Cause by that time the word had spread around about what I was doing. And I was enjoying it too, because I couldn’t imagine what I was doing, but it seemed to be right.

That’s beautiful.

I have always asked God to direct what I do. And to pick something for me. And evidently he wanted me to play this tambourine. That’s the way I rationalized it, (and said) “Okay, this is what he wants me to do.” I’d rather do what Lionel Hampton and Terry Gibbs and Red Norvo are doing. But if this is what he wants me to do, I’ll do it. And man, when I said that, everything went crazy. It was just amazing. So that night, I was introduced to Marvin…(he) was sitting there, (and Fuqua) said, “This is my brother-in-law Marvin Gaye,” and we shook hands, and (Fuqua) said, “And you never heard about him?” I said, “I’m sorry, but I haven’t. I said, “But I’ve never seen a guy in a green suit before either.”

That’s what he had on?

He was wearing a light green suit. And Marvin looked at me (and said), “This guy’s crazy!” I didn’t mean to insult him. You know, everybody was trying to be like Miles Davis. Speak what’s on your mind, regardless of where it falls. I was just being honest with him, I’d never seen a guy in a green suit.

Marvin kinda had dreams of being the next Frank Sinatra at that point, didn’t he?

Naw (laughing). He liked jazz, period. I would say that his area of attention was more like Nat King Cole.

The reason I say that is because, moving forward, after I got with him, a few months later they sent for me to come to Detroit. But I told them I’m not gonna leave my band to join Marvin. No. They said, “We’ll hire him too to get you.” I said “Well, okay.” Charles Harris played the organ, as the leader of the band. But the thing is, he was a tremendous vibraphone player. I was learning a lot from him. So it was more than just a gig to me. It was enriching my skills, my theory.

What originally got you interested in the vibes?

I wasn’t interested in none of that. I wasn’t interested in music, period.

Really.

No, back in ’52…somewhere ‘round in there, I was living in North Philly. With my brother. Because my mother had domestic work that she did. And she was working in Great Neck, New York. So it was just my brother and I and his family, and he was like bringing me up. My dad wasn’t there.

He was a little older than you?

Oh yeah, Al was about six years older than me. He was a person I just admired so much because he was a wealth of information (while) raising me. So one night I was just disgusted. I had the apartment up on the third floor of his house, and I got down and asked God to help me, because I was thoroughly disgusted (at) raising up in the inner city, and all the stuff that goes along with it, I said, “This is crazy. I’m not happy at all. Something for me to do.” Because I wasn’t happy. And I’d already walked out of high school, you see.

Okay.

I just let it lay. I asked Him to help me. When I look back on it, I could see the movement in his direction, and I said, “Well, this is funny,” I started doing different things. I didn’t feel it, but he was maneuvering me in the music mode. The first thing that came about, was here I didn’t know anything about music, and I wrote a song called “Everlasting.” And I had Nat Cole in mind when I wrote it. Or when I sang it to a person that could play piano and write the music down. As I’m looking at all this, one thing I always had, I had an inquisitiveness about things that were positive and how they got to be positive. They just drew my attention. He was answering my prayer all the time. And then the next thing you know I got this song under my arm.

How old were you at that moment?

I was in my teens.

And you had never played an instrument before?

Never, never, never, never. I had a thing about me, I used to talk to God a lot, because I never had a person that I hung with. And the gangs and all of that, I never got into that because I was around it, but it never kept my interest. I wouldn’t hang with them. For one thing, I couldn’t do that (because of) my brother. ‘Cause by now, talk about a hero. Here’s a guy that was working at a restaurant and trained himself to end up being the head chef. From dishwasher to head chef. And he had another skill, he could draw. He’d draw from memory…from your mind! And he had a little thing that he did. Mom had a big bible, it had big old gothic pictures of biblical figures. And he used to draw those figures on glass. He’d paint them on glass with a little brush. And I’m talking about them being identical. But we just took that as being something he did.

That’s amazing.

He got tired of that food business. The next thing I know, he’d joined the police department. And so I’d hang out with my friends sometimes, and we’d be in the park, and they used to talk about this policeman, this Black policeman, who (would) ride a horse! I said, “Oh? What’s his name?” They said, “We call him Cheyenne!”

What was it like when you first got to Detroit? Was it fun?

No. Because remember, I was leaving home to go to work. And I had to be successful or I had to go home a loser.

Okay.

My whole purpose was to buy my mother a house. We were always living with her relatives. I said, “I gotta make this work.” So I asked God to help me. I said, you know, “Help me do the right things.” He knew, when I got there they had four vibe players already. In fact, the guy I went there with, Charles Harris, was a vibe player. But he played organ excellently. When I got there, I said, “I got to do something else here.” But I had already explored the tambourine, you see.

How did you get switched to that?

Well, what happened, about me being a percussionist, I’m over there behind the vibes. The first song I played vibes on that was a success was “Where Did Our Love Go” by the Supremes.

A classic! (and their first #1 hit on the Billboard Hot 100, produced by Brian Holland and Lamont Dozier)

Well that’s the first song I played vibes on. I don’t even know what the other song was, (but) they saw my tambourine and said, “Can you play the tambourine?” I said, “Yeah.” So I started playing the tambourine and I looked up in the control room and there was about eight people in this little joint, little box, looking at me play tambourine. They’d never seen anything like it. And so, I said, “Wait a minute, I already asked God to help, is this it?” Whenever I ask God for something, I look for results. So ain’t got nothin’ to do with my faith, forget that. I’m looking for results. ‘Cause I know he’s there. (Laughing)

(Laughing)

When I saw what they were doing, remember I couldn’t explore, because I don’t know the instrument. I don’t know my limitations. So I’m playing the tambourine, and when I got finished, they were falling out. They said, “Man, can I get you to overdub on my session?” And Earl Van Dyke said, “Man, Jack doesn’t know what you’re talking ‘bout overdub, he’s a nightclub boy!” That’s where I met Earl, in Atlantic City. I was playing vibes. And so I said, “Yeah.” I say yeah to everything. Just to stay. ‘Cause I knew one thing. Marvin Gaye was lazy. He didn’t want to work. He just had natural skills, man.

So you couldn’t count on him being out on the road.

Oh, no! But I didn’t get that ‘til I got there. And then he (Marvin) talked to Smokey (Robinson), and Smokey came to me and said, “Jack, anytime they have a session and you’re not on it, call my office.” And I said, “Well, okay.” But I never had to do that, ‘cause after they heard me play the tambourine, they were lined up waiting to get me to overdub. One song here, two songs there. Norman Whitfield was a tambourine player.

I never knew that.

Oh, yeah. And so, when he heard me play, he said, “Hey man, I got four songs I want you to overdub on.” I said, “Really? Okay.” I don’t even know what they were. “Needle In A Haystack” was one (the biggest-ever hit by The Velvelettes, released Spring, 1964).

Wow.

I played tambourine on that. And then a couple other ones, you know. But it grew like a wildfire. So now, I’m working every day the Funk Brothers are working.

That’s so cool.

At that time we were getting ten dollars per song. And my pockets was fat, ‘cause how much I was doing.

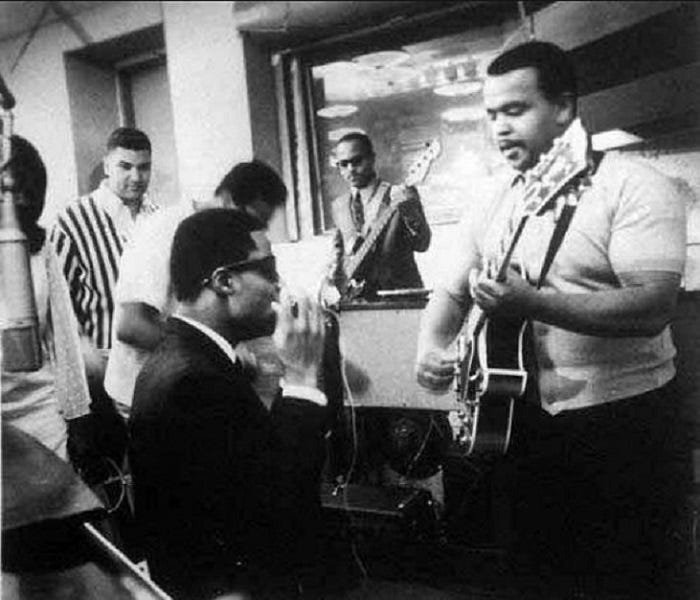

Was Robert White in the band then?

Oooh yeah, man. One of the most overlooked talented players in there.

Amen to that.

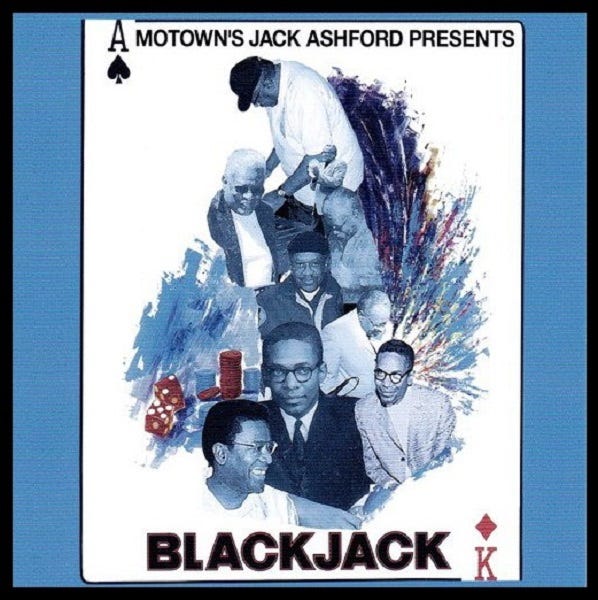

This guy…did you hear that album I did called Blackjack?

Of course! 1978…

Robert White did the arrangements, man.

You guys co-composed the album.

Yes indeed. My wife and I wrote the music.

Okay, she did all the lyrics, and you did the music.

Yeah.

And he arranged the whole thing. It was brilliant! (The ultra-rare soundtrack was released on S.E.S. Records, and included an epic main title theme plus funky instrumental jams like “Freemont Street” and the album’s masterpiece “Las Vegas Strut.” An original vinyl copy sold for more than $3000 on Discogs in late 2019.)

The key…you would never think he was a guitar player like that. Sitting in there, session every day. But now, let me explain something to you. Here’s a guy that’s a session musician. Who’s playing other arrangers’ music. Techniques. All those things that they do, he’s interpreting it and playing it. So wouldn’t he be a good arranger? Things he picks up from everybody he works with.

Totally.

I didn’t understand that until he did Blackjack. I didn’t know he did that. But I tell you who loved him.

Who?

Marvin Gaye. Marvin knew he was good. But see, Marvin wasn’t a producer, so he couldn’t say anything. And let me tell you something. Motown was a great place to walk in there and go undiscovered. And be a superstar. Barbara Streisand wouldn’t have gotten a chance to do a demo in there. ‘Cause if you wasn’t coming in there with the right credentials, you didn’t do anything.

From what I’ve read, Marvin really tried to stand up for people like Shorty Long at Motown.

Well he put our names on the album. That was the first time that ever happened.

Oh really?

Yes indeed. He was the first one to put the Funk Brothers’ names on.

On What’s Going On?

Yeah. ‘Cause that was his debut album as a producer. That’s why he didn’t use all them Funk Brothers (before), you know.

I know “What’s Going On,” the song, was recorded over several sessions…

Here’s the thing. What I’d never done before. He didn’t end the song like you ordinarily end it, let it fade out. He would say, hold like a fermata at the end, just to sustain that note. And start talking. You don’t talk in the session. Well, we did for him. First time I’d ever done that. And that’s why you hear in one of them songs, I was in a sub-room, Eddie “Bongo” was out in the main room. And (Marvin) said, start talking. And I came out of that room and you hear Eddie say, “Hey man, what’s happening!” Well he had a mike sitting there miking the drums, so it picked his voice up very distinctly. But you couldn’t hear me ‘cause I’m coming from another room. So I said, “Yeah, what’s happening.” He said, “What’s happening, man! Everything is everything!” That’s Eddie “Bongo” Brown!

Cool.

That’s him talking. So, for those who never heard him, that’s what he sound like. Because here’s an awful thing that happened. When Motown sold out to Universal? Or whoever it what that bought it first, whatever that was about. But anyhow, they had to get the tapes ready. From the tape library and transfer the physical tapes. So what happened was, the engineers…oooh. How could they do this. They edited the daggone tapes. And put leaders in between the songs.

Really?!

All the banter that went on the sessions, in between. Gone.

Oh, wow.

All of those years. Well they called themselves being efficient. That’s why it was expedited, and you know, everything leadered up. Yeah, but just look what you’re doing.

That’s erasing history.

Absolutely. I’m gonna tell you something about that. You don’t know you’re making history when you’re doing it. ‘Cause you’re living it. No one knows that. Always remember that. No one knows you’re making history. ‘Cause you’re living it. You’re creating it. And they didn’t know. I mean, I pity them. Because they did erase a lot of…to know what those guys sounded like. The only voice that I know, that you can hear, was that on “What’s Going On.” When Eddie Brown says “Everything is everything.”

Well, the world lost a treasure trove of musical history and knowledge when that went down. And that’s a real shame.

Yes it is. (And) no one else can tell you that, man. But here’s the deal, with as much knowledge as I have about Motown, when Allan Slutsky did Standing in the Shadows of Motown (the 2002 documentary), he never consulted with me.

Really?!

Nope. I was there when we went on strike against Motown in London. Ain’t nobody know about that, I’m the only one living that was on the musicians’ side.

What year was that?

1965. When Motown went over and was introduced to EMI. And the distributing company over there.

So you guys were just tired of being underpaid?

No…we did a date with Dusty Springfield while we were over there. Martha Reeves did. And we recorded it in the studio and everything. Berry’s sister Esther didn’t want to pay us for the session. She said, “Well, we already paying you for comin’ over doing the (tour),” So what’s that, that don’t have anything to do with this. So she said, “We’re not gonna pay you for that.” So Earl Van Dyke said, “Then we ain’t gonna play.” And we were in the dressing room, and the place was full. The Supremes getting ready to go out, and Berry’s wondering, “Well, where’s the band?” ‘Cause the curtains are closed but there’s no musicians. And so Earl told him what happened and he said, “Oh, you gonna get paid, just go on out and do the job. I’ll straighten it out.” But we went on strike.

Good for y’all.

But the thing is, Allan didn’t know that. And when he was doing the movie…you know what I’m trying to say? And Uriel Jones wasn’t there. Eddie Willis wasn’t there. And these were the key people…

He should have consulted with everybody who was living, to get the full story. I mean, that’s just common sense.

It is, (but) not with them guys. I saw ‘em do some scurrilous stuff to the Funk Brothers, boy. Well, he was getting so much information, negative, “Oh, the Funk Brothers was taken advantage of…” that he said, “Well, then can we get a little bit too.” That’s what happened.

That doesn’t sound right. My only experience was I saw the documentary in the theaters. I wasn’t nearly as educated about the history of soul music and Motown at the time, but thought it was a really cool story. I’ve since read that (the two of you) definitely had a falling out, and it sounds like you had pretty good reason.

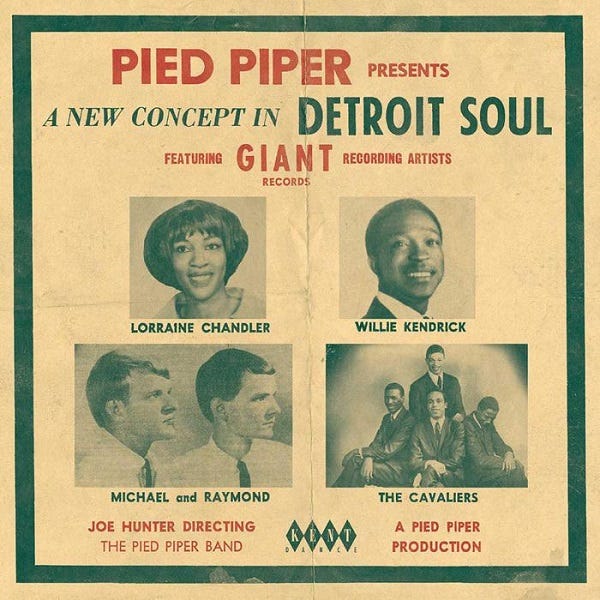

Well I didn’t want to say anything, because I was probably the most experienced person in the Funk Brothers ‘cause I had my own record companies. Pied Piper, and Just Productions, you know, I had all of that. So I knew more about the business itself. Johnny Griffith. He was the keyboard player. He was (also) my artist (for Pied Piper). Alright? I’m the one that got the legal representation to break the management contract that they had on us, and so then, they had to watch me. Because I wouldn’t buy anything. And so what happened is…it’s not what it looks like. The widows…unbelievable. Earl Van Dyke’s wife just passed last year.

Oh, I’m sorry.

And Jamerson, all of that.

What you’re saying is that these folks’ families are still getting ripped off.

Oh yes, of course! Haven’t received a check yet from Standing in the Shadows.

That’s not right.

(Laughing sadly)

Search our full archives

So, as iconic a figure as you are in the development of Motown and the Motown sound, you’re also one of the greatest songwriters and producers of your generation, if not of all time.

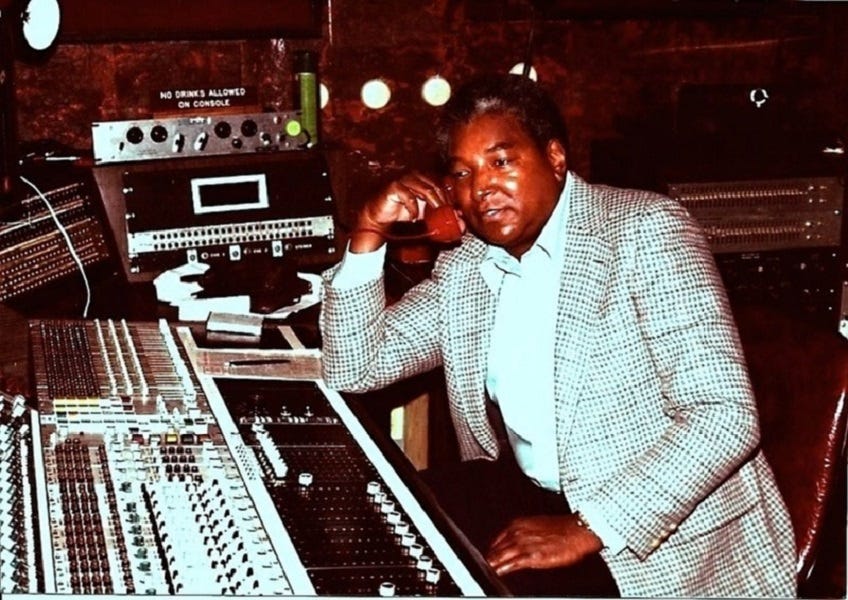

Well I learned that from a guy at Motown. His name was Mike Terry.

Right, Andrew “Mike” Terry!

Baritone (sax). Absolutely. He’s the first one I started producing with.

You guys wrote a lot of songs together.

Pied Piper Productions? That was us. Oh, man, all those baritone solos (on Motown records), that was him!

So you and Mike Terry, and Joe Hunter, and Herbie Williams, all of you were in Motown’s backing band, right?

Well, the thing about it with Joe Hunter, I never did a session at Motown with Joe Hunter.

He was a little before your time?

Yes, he was. The thing about it was, Joe Hunter ended up working for me. He was my A&R Director. But he had already left Motown and Earl Van Dyke came in.

And replaced him?

Right, because Earl had just gotten out of the service. So what happened was when he did that, naturally I saw Joe, but Joe wasn’t there when I got there in ’63. But, Joe Hunter was the very first Funk Brother. He was the first person that was willing to work along with Berry and his fledgling company. Under those conditions. You know, because you get a lot of people saying how we didn’t make any money, like we should have made, and all of that. But wasn’t no one making any money. Because there was no iconic record company there.

So he was really Motown’s first bandleader.

Absolutely! That’s exactly what he was. Joe Hunter, a lot of that you have to attribute to his desire to succeed. Because not only was he working at Motown, he was doing band arrangements for B.B. King!

When you decided to set up Pied Piper Productions, was that your company? You were in partnership with these other guys, but were you the one calling the shots?

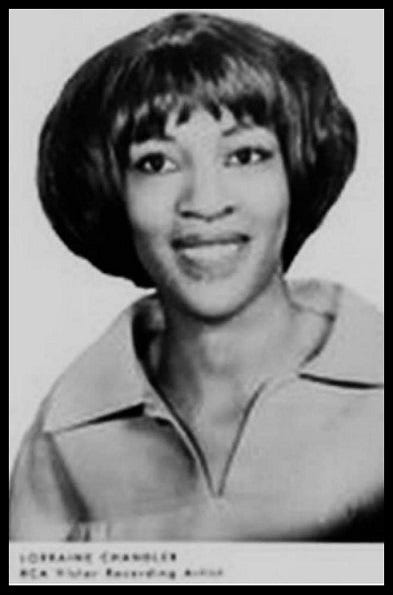

No, no, I was only in partnership with one of them. Mike Terry. (He) and I decided to do stuff because he’s so talented, you know. Like for instance, our first artist, I know you know about Lorraine Chandler.

Of course. How did she come your way? How did you meet her?

I met her one time when I was going to work at Motown, and she happened to be standing outside with some other young girls, and the Temptations were there, getting ready to go in and overdub. We had just finished a session. So the next producer was coming in with a vocal overdub. And so, she knew Otis.

Oh right, they were family friends somehow.

I didn’t know anything about their relationship. He just said, “I want you to meet somebody.” She said, “Oh, how ya doing.” And when she spoke, I was surprised, because her voice, the sound of her voice was so big. And she wasn’t hollering. (Laughing) She was just talking. And so I said, “Well okay,” and we exchanged numbers. I said, “A friend of mine (might want to record you)” (but) I didn’t mention Mike ‘cause the guys were standing there, you know. And then she had a friend, we named her Mikki Farrow but that wasn’t her name. I forgot what her name was.

And you guys recorded her too.

Yes indeed. What happened…we recorded both of them. But I think “What Can I Do” was Lorraine’s first record. With (backing) by the Funk Brothers.

That’s a great record (an upbeat soul gem), and you co-wrote that with Mike.

Maaann. That’s right, that’s right! (Laughing)

It was backed with (the superb jam) “Tell Me You’re Mine,” and you guys co-wrote that one, too.

But it didn’t chart nationally. Was it a regional hit?

No, lemme tell you, Berry Gordy heard that record and got mad, and put the brakes on it. Even in Detroit, we couldn’t hardly get any airplay unless it was four or five in the morning.

I knew there was something wrong! ‘Cause that is a great song!

It was a big record, man. That was a fantastic record. And after you hear that solo Mike Terry put in there? C’mon, man. That’s classic Motown. In fact, we used almost (all) the Funk Brothers to do it! Except for Jamerson.

He wasn’t on there?

No, we used Bob Babbitt.

Her follow up, “I Can’t Hold On”…

Oh, yeah. (Laughing)

I think that is the best record she ever did, and you co-wrote that one too.

Absolutely. Well then, by that time, she was hanging around the studio where we used the facility, and she started getting into writing. ‘Cause she wasn’t a writer. Her father didn’t want her in that business. But after he heard “What Can I Do”? He was convinced. He said, “That’s my daughter!” (Laughing) She sang it like a pro. Have you heard it lately?

I have, that’s a great song. But I’ll listen to it again tonight. “I Can’t Hold On,” for my money, is a masterpiece, and RCA, when they originally released it, they put it out as a promo with the sides flipped. I don’t know why they did that.

Well that was such a bad deal we did with RCA. I mean, the only thing missing in the deal was they didn’t put a gun in my face. That’s the only thing missing out of that whole scenario. Like, “I’ll give you a deal, if you go around here on Fifth Avenue, and go to the basement, and there’s a guy standing out there with a mask on, go in there, and if you sign with him, I’ll sign with you. Okay?” (Laughing)

That record is selling for a hundred and fifty bucks today, original copies…

Wait a minute! You just made me think of something. You said $150 for that record?

For that particular original record, yeah.

What do you have by Eddie Parker? That Lorraine co-wrote (“I’m Gone,” 1966).

I don’t have any prices on his.

How about $18,000 a copy?

Oh, really? Wow. Because I was gonna say, $150 is one of your lesser-priced records. Some of the ones I know about are selling for two or three thousand. But eighteen thousand. Wow!

Why don’t they give me some of that money? (Laughing) Did you know Mike Terry and I did (The O’Jays)?

I saw that you guys had co-written some songs for them.

Absolutely. We did the O’Jays, we did “I’ll Never Forget You.” When they were on Imperial.

You guys produced that record?

We wrote and produced it. We got the publishing on it. In fact, listen to this. I didn’t want to use Eddie Levert as a lead, ‘cause people were used to hearing him. And he didn’t have a hit. So I had Walter (Williams) sing the lead on it.

That’s cool, because you know, he has a great voice…

That’s why I used him!

It took Gamble and Huff a little while to figure that out.

Well see, I didn’t want to produce something on him that would be beyond his ability to sing. So I wanted to produce a record that was in what I (heard). I said, “This guy got a nice voice back there, let’s pull him out.” And it worked.

Was the reason that you and Mike Terry decided to form Pied Piper and that Joe came on board, and Herbie Williams…

Well, we hired Herbie.

He was (one of) your arranger(s)?

That’s all. My partner was Mike Terry. And Mike Terry schooled Bobby…you ever hear of Bobby Martin?

Yeah, yeah, from Philadelphia International (Records). He was (their) key arranger.

Let me tell you something. He was a tremendous vibraphone player.

Oh yeah, right.

Well here’s the thing. I knew him from when I lived there.

Okay.

He got in touch with me in Detroit and asked me, could he get me to talk to Mike Terry about string composition, how to do that. How to do those strings to get that fat sound. He didn’t know whether we used eight violins and two violas, and two cellos, or…they didn’t know.

Because he was trying to figure out how to do it for Gamble and Huff.

Absolutely! And so they flew Mike and I down there…

Wow.

…and we did the date. And he schooled…he stayed two days teaching Bobby how our technique was.

Wow. That’s incredible! So you helped give birth to the Sound of Philadelphia!

Absolutely. You’re the only one I’ve ever told that to.

Bobby Martin (was) the unsung (architect) in addition to Gamble, Huff and Bell. But you’re the ones who schooled Bobby Martin!

Your autobiography that you wrote with your wife looks fantastic.

She’s a retired schoolteacher. And Sunday school teacher. And basketball coach. And author. She has a book out (now).

Another book besides the one y’all did together?

Oh yes, she’s (done some) on her own. There’s One In Every Family (2022). It’s very interesting.

What’s it about?

It’s about, you know, in every family you always got that one person that everybody gotta watch ‘cause he’s tryin’ to get over on everybody. That type of thing. It’s fiction.

Charlene (in background): Realistic fiction.

Is this the one with the wife with the five husbands? (Laughing) That’s another book.

I was listening to all of your solo album (today), which I had not done before, I don’t think it was ever online in full, and I’ve never seen a copy in the wild, even though I’ve been collecting records for many years. But the entire thing was amazing. So many good songs. And you (and Charlene) wrote the closing cut together, “Funky Disco Party.”

Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah. That’s exactly right.

That was a funky jam right there.

You like that?

Oh yeah!

Well that was influenced by doing it at Marvin Gaye’s (studio). You see? Because we had just finished “Got To Give It Up.”

One of the greatest party records of all time.

You see what I’m saying? You do know I defended him against Robin Thicke.

No.

You didn’t hear about that?

I saw something about it, but what happened?

I was on MSNBC with Chris Hayes. They put that record out, “Blurred Lines.” Yeah, the line is blurred ‘cause he blurred it out!

(Laughing)

That’s what happened. (Laughing)

So he ripped off “Got To Give It Up” in that song.

He ripped off that, and what happened was, the irony of it is, Marvin’s wife, before I went in and gave a deposition, was thanking me, she said, “Jack, I want to thank you for what you did,” and then she died, so they got about $7 million, I didn’t get anything.

Oh, man.

I didn’t mind. ‘Cause Marvin was my friend. I didn’t do it for the money. I didn’t know there was any money there. I just told them what happened. And I had an instrument that I invented called the hotel sheet.

I was gonna ask you about that.

Did you hear about that?

Well, because I know that the hotel sheet got included, shrink wrapped, in copies of your record.

Right. And what happened was, when I got my star (on the Hollywood Walk of Fame), when Stevie came up to the dais to speak, he leaned over to me and said, “I still got my hotel sheet.”

(Laughing)

And it was so funny he said that, I said, “Long time, man!” (Laughing)

(Laughing)

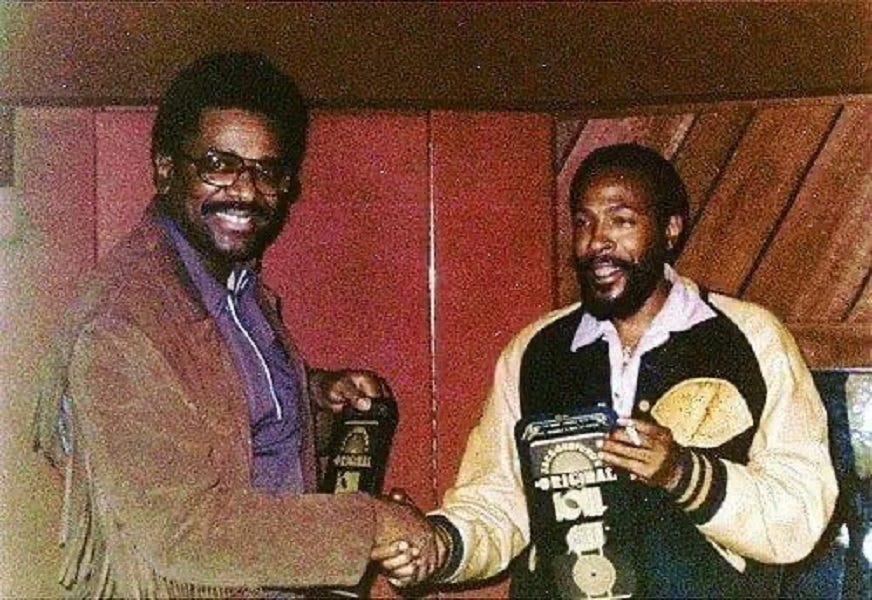

And he has it, you know? I got a picture of Marvin Gaye holding it.

That’s so cool. On the title track to the album, is the sound on the title track, is that the hotel sheet?

I don’t even know. (Laughing)

It’s a very distinctive sound.

Boop-boop-a-boop-boop (mimicking the hotel sheet)

Exactly! Exactly! You hear it all throughout the track. That’s the sheet!

That’s it.

Wow.

(Laughing)

That’s so great. You also played that on a Mighty Clouds Of Joy record.

Ooh. I played it on so many, because after people starting hearing about it, people were calling Motown up and asking, can they buy a hotel sheet. They didn’t know what a hotel sheet was!

(Laughing)

‘Cause it’s just a piece of plastic.

How did you come up with that idea?

Well, the first time I used it was on “Got To Give It Up.” For Marvin. I put the tambourine on “Got To Give It Up.” He said, “Jack, what else you got in the bag?” I said, “A couple of things here.” I pulled the hotel sheet out and said, “Get a balance on this.” So I played it for a minute and the engineer got the balance on it. Art Stewart was the engineer (and producer). He got a balance on it, and then I put it on “Got To Give It Up.”

Wow. (Laughing)

He said, “Man, that is unique!” He said, “What d’ya call it?” ‘Cause it got to be put on the session notes, what the instrument was, so it can go to the liner notes. So I said, “Uh…just call it a hotel sheet.” The reason I said that is because after you’re on the road, the sheets in the hotel feel like plastic.

(Laughing)

And that was the reason I chose that name. And it stuck. So people start calling up Motown, asking how can they get a hotel sheet.

That’s wild! I just figured that it was like, you know, the things you hang on the door.

No, this is about 8 inches long, 6 and a half inches wide.

Yeah, I could tell it was an enormous one, I just had no idea where the name came from.

I took a picture (with it) on one of my albums. And a woman standing behind me at the door. That was a blow up version of it. ‘Cause it wasn’t that big.

It had to fit in the album.

There ya go. And so when I got finished using it on that date, “Got To Give It Up,” Marvin Gaye took a picture. He said, “I got to get a picture with this.” And we took a picture with him holding the hotel sheet.

My personal favorite from that record is “This Ain’t Just Another Dance Song” (with a smokin’ instrumental version that spotlights Funk Brother guitarist Robert White’s signature sound, who played on the Hotel Sheet LP).

Oh, you like that?

Yeah! You co-wrote that with Lorraine Chandler and Charles Leverett. Who was Charles Leverett?

Ooh boy, that’s history. That was a friend of Berry Gordy’s. His wife worked for Barney Ales.

And you went to work for Barney Ales in the seventies too, right?

I did. I worked for Barney. But he was just setting up a ruse. So when we went back to Motown and Berry said, “Okay, well come on back,” and he (said), “Yeah, but I got a company now.” (Knowing Gordy would ask,) “Well what’s it going to cost to dissolve it?”

(Laughing)

All kind of skullduggery. And so man, I said, “This is crazy. He never intended to make this Prodigal Records a success.” He didn’t care about that.

Wow.

But he didn’t tell me.

(Bookmark the link to this post and check back for the must-read rest of this interview, which is still in the editing process but will be added soon. The YouTube playlist contains all songs to be featured.)

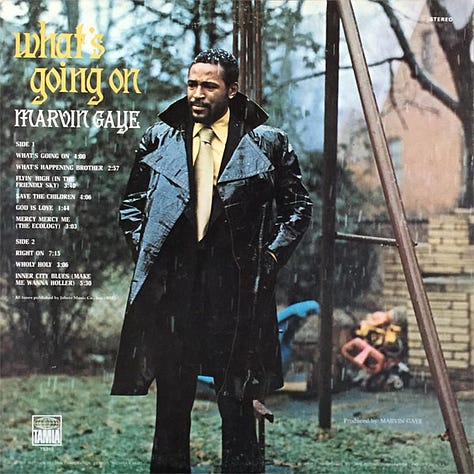

If you don’t already own them, consider adding to your collection the essential, highly recommended CD compilations of Ashford’s recordings with Pied Piper Productions (Pied Piper Presents A New Concept In Detroit Soul Vol. 1, Pied Piper: Follow Your Soul Vol. 2, Pied Piper Finale Vol. 3). Or stream/purchase Vols. 1, 2, and 3.

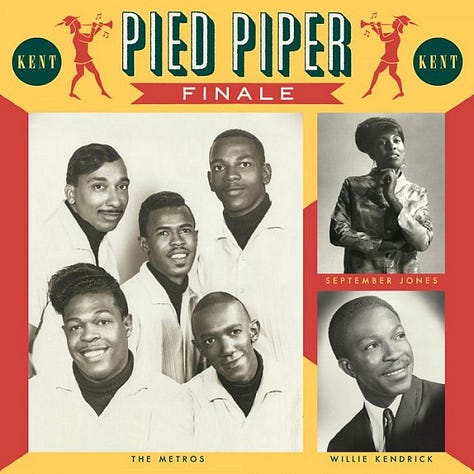

Also, Just Productions (Vol. 1 on CD or LP, Vol. 2) or stream/purchase Vols. 1 & 2.

Happy 90th Birthday to the great Jack Ashford.

Further info:

“Musicians Joe Hunter and Jack Ashford,” interview by Terry Gross, Fresh Air, NPR, October 18, 2002.

“The Players Behind The Motown Sound Recognized At Last,” The New York Times, November 10, 2002.

“Funk Brothers Come Out Of Motown's Shadows at Last,” Washington Post, November 15, 2002.

Motown: The View from the Bottom, by Jack Ashford with Charlene Ashford, Bank House Books, 2003.

“Jack Ashford oral history interview,” NAMM.org, July 15, 2013.

Detroit 67: The Year That Changed Soul, by Stuart Cosgrove, Polygon, 2016.

“Memphian Jack Ashford recalls his work on Marvin Gaye's 'What's Going On',” The Memphis Commercial Appeal, May 14, 2021.

“Mr. Tambourine Man: Finding The Frequency in the Snakepit,” by Adam White, West Grand Blog, June 4, 2021.

#soul #funk #Motown #FunkBrothers #PiedPiperProductions #JackAshford

Brilliant interview, Jointz! Cheers to you and happy birthday, Mr. Ashford!

"Shar" is a fab track. I've never heard it before. I first heard the Eddie Parker tune in the British film, 'Northern Soul.' It's an absolute floor stompin' barnstormer of a track. But, $18k? Wowza! 😳