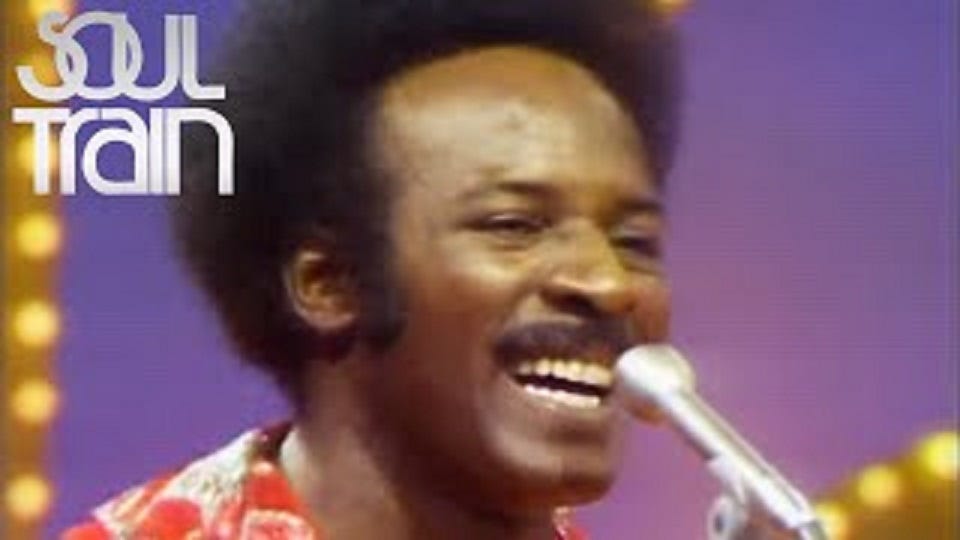

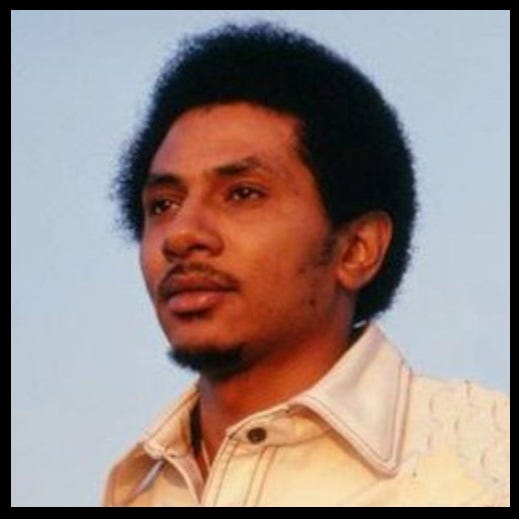

Exclusive O'Jays Interview with Walter Williams (born August 25, 1943)

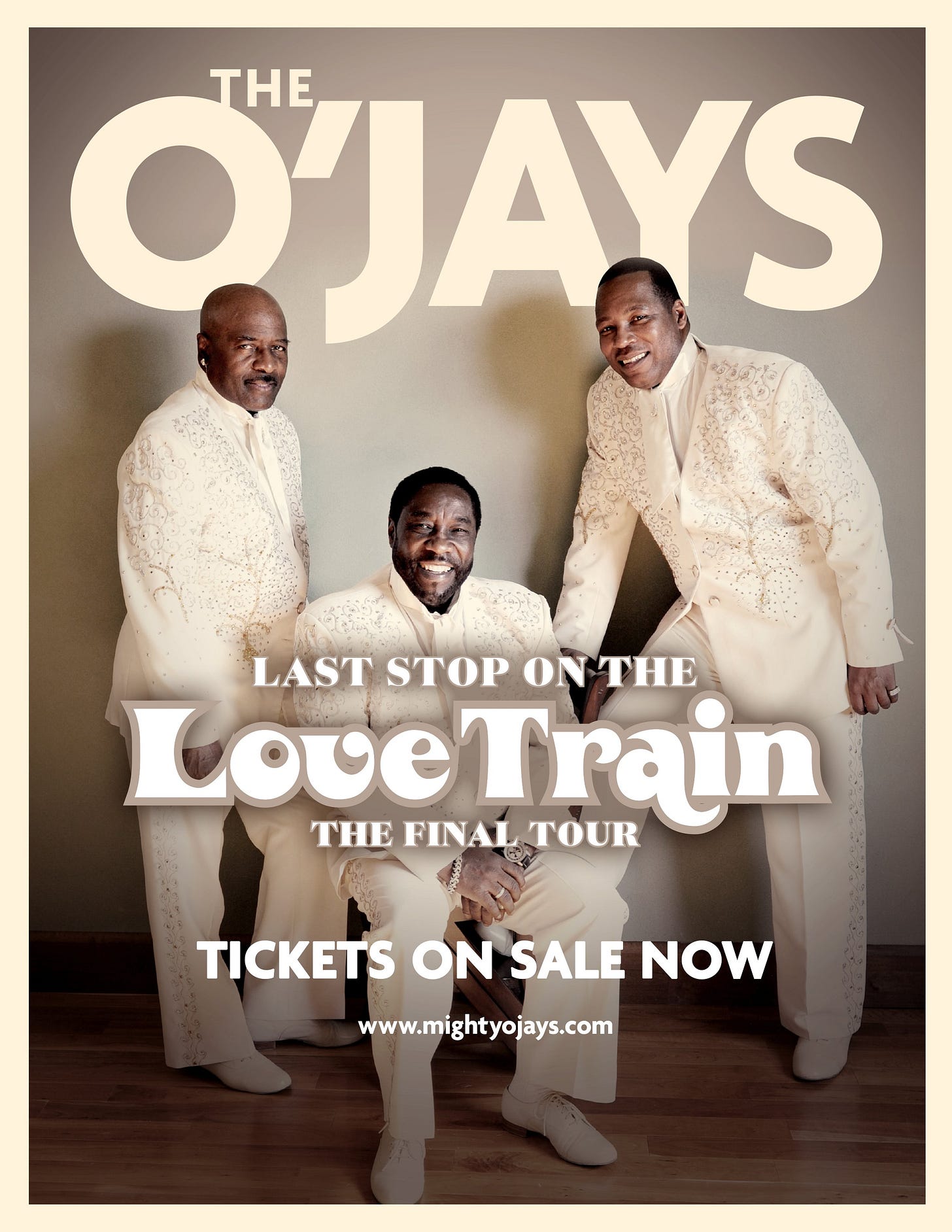

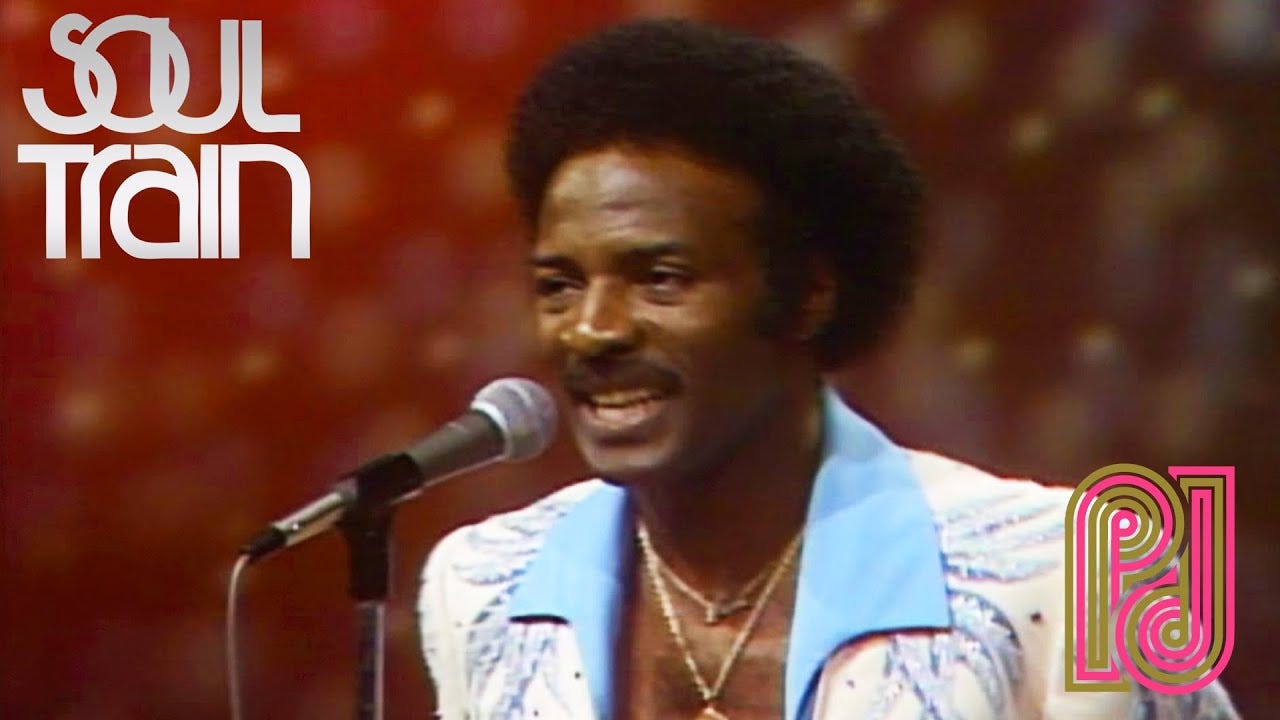

The legendary O'Jays co-founder reflects on the group's history and cultural legacy as they play packed shows on their Last Stop On The Love Train farewell tour.

View most updated version of this post on Substack.

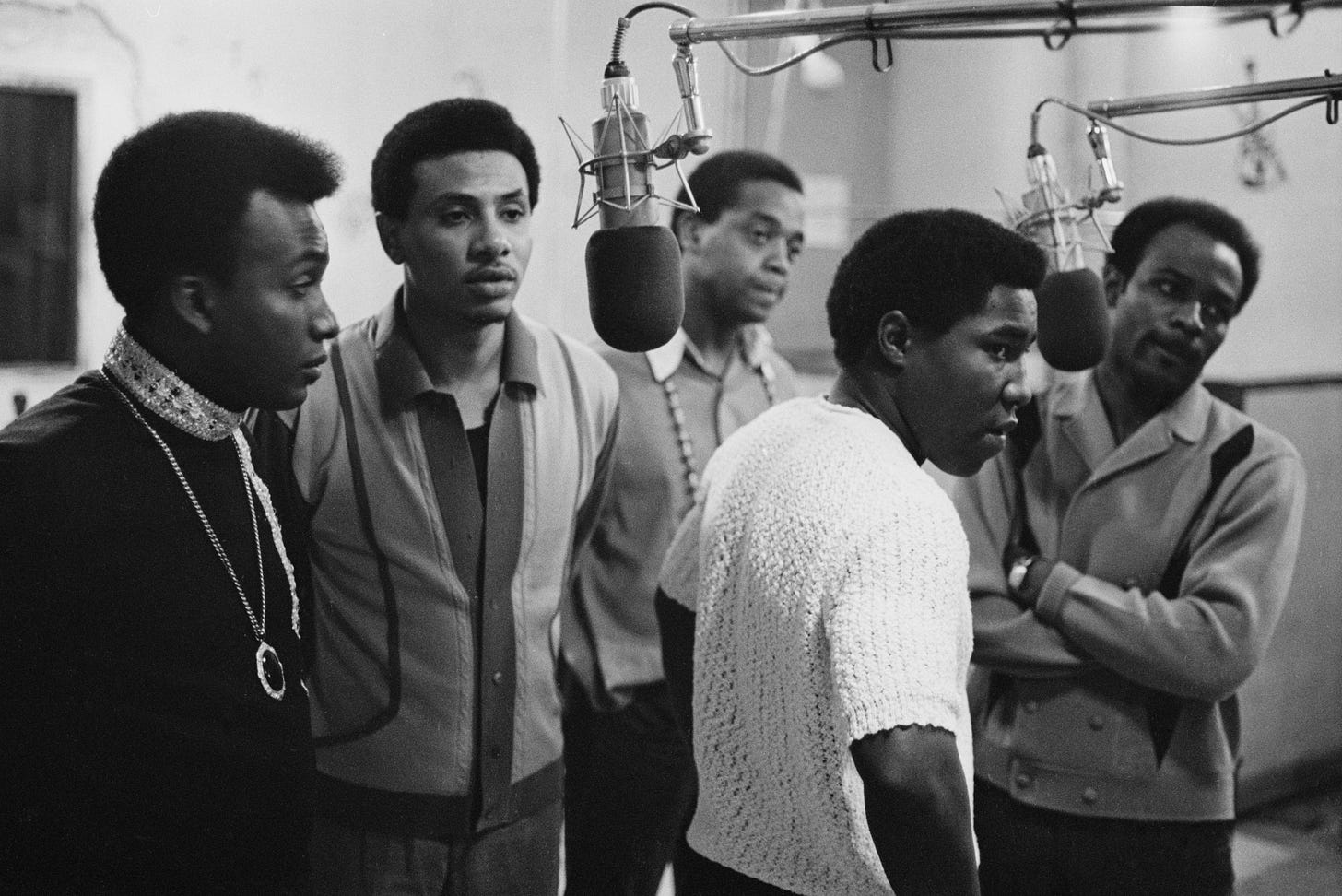

The great singer/songwriter and producer Walter Williams Sr. is a founding member of the mighty O’Jays, one of the most iconic R&B groups of the 1970s and beyond.

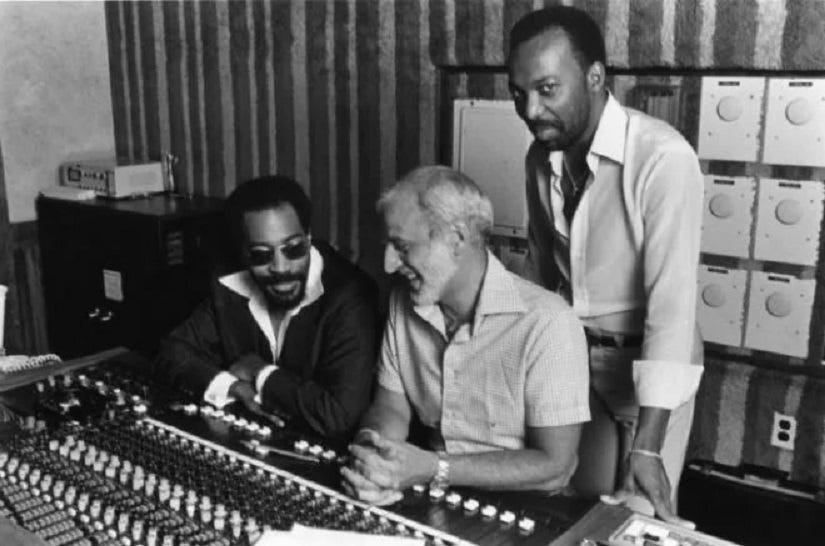

Formed in Canton, Ohio in 1958 by Williams and his childhood friend Eddie Levert, the group’s other original members included William Powell, Bill Isles, and Bobby Massey. They recorded throughout the sixties, but shot to worldwide fame in 1972 with Back Stabbers, their first album on writers & producers Kenny Gamble and Leon Huff’s Philadelphia International Records (PIR) label.

Its title track hit #1 R&B, a feat they duplicated with the album’s next single “Love Train” which also went to #1 on the Billboard Hot 100, becoming their biggest hit and best-known song. It was the first of eight gold or platinum records they released over the rest of the decade, helping bring socially conscious music to the top of the charts as the primary vehicle for many of Gamble and Huff’s powerful message songs. See our earlier posts on Eddie Levert, Kenny Gamble, and Leon Huff for more on the group’s history.

To commemorate his 80th birthday, Williams gave an exclusive, detailed interview to Micro-Chop and Jointz Of The Day about The O’Jays' current Last Stop on the Love Train farewell tour and their career and cultural legacy.

(Interview conducted by DJ Dyn-O-Mite for Jointz Of The Day, edited by Gino Sorcinelli of Micro-Chop)

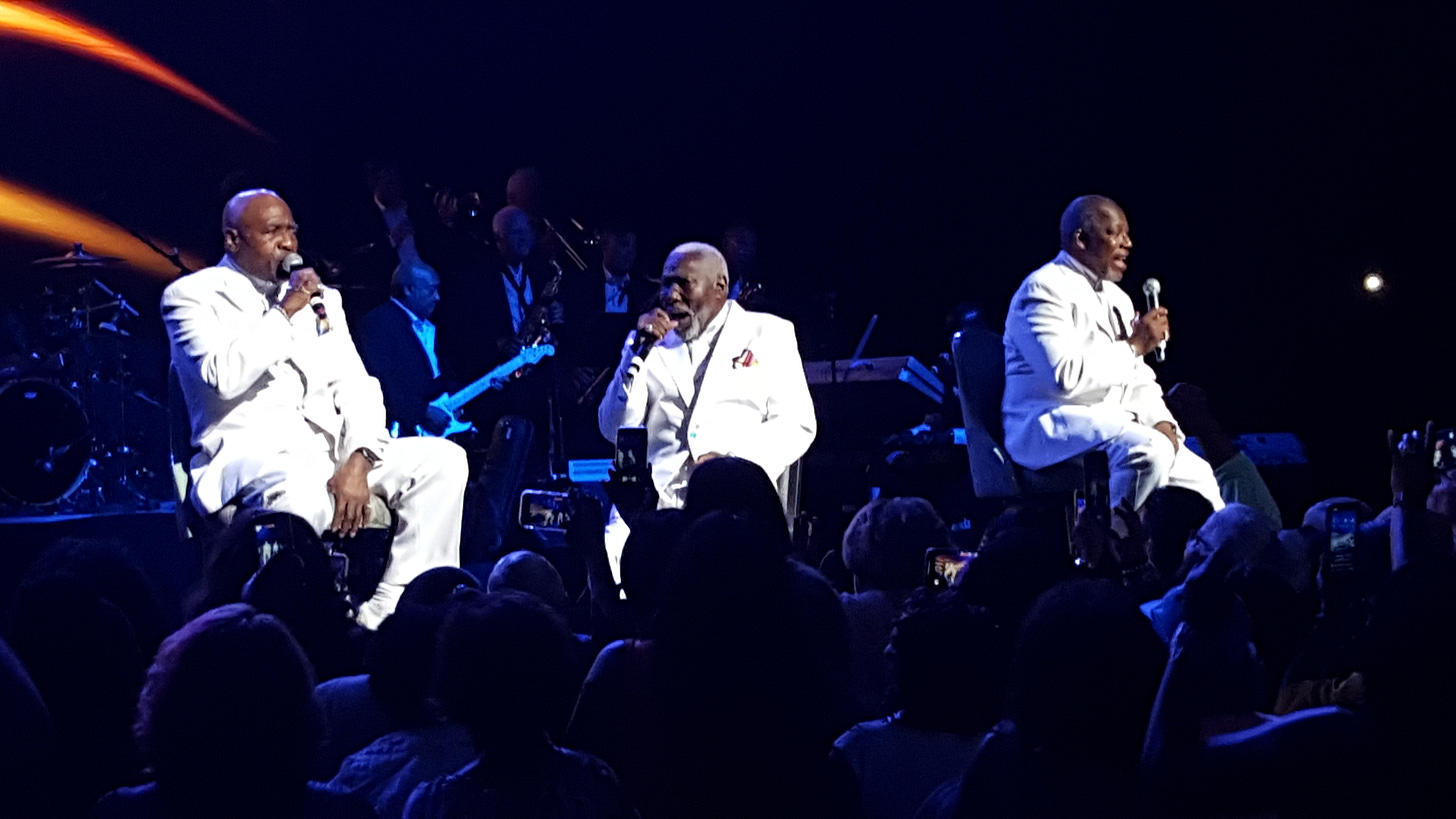

I’ve been a big fan for a long time, and I saw you guys two nights ago in Connecticut. You put on a great show.

Thank you! ‘Preciate that.

There was so much love in that room for y’all.

(Laughing) I like the way you put that. That helps. That really helps.

You could feel people’s excitement and enjoyment and everybody who I talked to after the show said you guys absolutely killed it and that you were just the best.

Well thank you. That’s really good to hear.

Are you going to miss touring now that these days are coming to an end?

I gotta say yeah, because this is what I’ve done since an early age in my life. I got my first contract at King Records when I was 16. And I’ve basically been on the road as much as I could since then, covering records and trying to make them bigger than they would normally be if I sat at home. So I’ve always tried to work. In the show, we’ve always included whatever product we had out, whether it was a big hit or not. We tried to make people aware of the songs being released whether they were being played on the radio or not. We always thought that would help, by putting them in the show and performing them. And we did other people’s hit records as well.

Like “Wildflower,” by Skylark.

Absolutely. Yes.

The ladies loved it, and so did everybody else.

(Laughing)

Your rendition, I guess you first put that on your live record back in ’73, from London.

Yeah, we did it live in London. They were the first overseas crowd to hear us do it. They loved it, and we recorded it. And it was a big one on that particular album.

Where were you born, Walter?

I was born in Canton, Ohio. 1943.

There’s conflicting accounts. Some I’ve seen said only Billy Isles had been born in Canton. I know Eddie (Levert) moved there from Alabama.

Bill Isles, now I didn’t think he was born in Canton. I thought he was born in North Carolina, and his family migrated to Canton, but I’m not sure about that.

They may have had it reversed, wherever I got that from. So you’re from Canton.

I’m from Canton. Now, William Powell was born in Canton as well. But he passed away in the seventies. And Sammy Strain took his place.

Did you meet William Powell or Eddie earlier than high school?

Oh yeah, I met Eddie when I was like eight years old. He was a year and a couple of months older than me. He moved into the neighborhood where I lived.

How did you first start making music together?

Early. I think we might have been ten, eleven years old. We sang gospel. My dad sang gospel and he kinda taught us a little bit then, and then later when we were entering our teenage years we got with him again because we wanted to sing at a friend who died in a car accident, Donald Jackson, we wanted to sing at his service. And my dad taught us the song. And then he would give us helpful hints along the way. He was my choir director at St. Mark’s Baptist Church. Eddie was also in that choir. But I basically had to be in that choir. Eddie didn’t, so he dropped out before I was old enough to dictate my own future. (Laughing) My dad was kinda strict.

Eventually while you guys were in high school, you formed your own secular vocal group, right?

Yes. Yes, we did. During exams, a lot of people would go to the cafeteria at McKinley High School and just hang out between exams. And we started…because the bathroom at McKinley was marble and it had somewhat of an echo sound in it that made sound better than you really were. (Laughing) So that helped. And that’s where we all got together and started, y’know, just harmonizing like we did on street corners and in front of places where they would have dances like the YMCA, like the Urban League, and some of the little juke joints in Canton. Just to get the attention of the young ladies. (Laughing)

That’s what it’s all about! (Laughing)

Yeah, man.

Well, you’re still doing it, because for “Wildflower,” I think every woman in the audience came down to the front of the stage.

(Laughing) Yeah, we try to get ‘em to do that! That was an idea that our band director Dennis Williams came up with, and Eddie and I helped him to perfect it.

Was your group’s very first name The Triumphs, or did you have another name before that?

No, not before that. We called ourselves The Triumphs. When we really had nothing goin’ on, other than being able to harmonize really good. And performing. We’ve always liked doing choreography. But a guy that played guitar for Dionne Warwick, he told us we should be moving, and not just standing. And we started making up stuff that we would see the dancers doing on the Dean Martin Show, the Ding-a-Ling Sisters, and choreography that we saw people doing on some of the entertainment shows like Hullabaloo and Shindig and that kind of stuff. We started making up our own moves.

And then, finally we got with Cholly Atkins. And he really brought it home. He was a choreographer. He worked for Motown. (Before that), he was with a team called Atkins & Coles. They were tap dancers. And they were damn good. Then he started doing choreography for Motown. He taught the Supremes, the Tempts, the Spinners, Contours. He taught everybody at Motown that would come to his class. Some of the guys, some of the groups, chose not to come to his class. But Michael Jackson went to everybody’s class, so Cholly tells it. And that’s where he learned a lot of stuff.

What year did you start working with him?

Ooh…It had to have been late 60s, early 70s. Definitely we were with him by ’72, with “Back Stabbers.” And that may have been the year, because “Back Stabbers” happened, and we needed somebody to give us a better look on stage. Matter of fact, we say the chemistry that made O’Jays happen was Gamble-Huff, Cholly Atkins, and Walter Williams and Eddie Levert.

Makes sense to me! (Laughing)

(Laughing) Those were the ingredients that brought it all the way home.

After the Triumphs, you became the Mascots.

Yes. That’s because (of) a guy at King Records named Sid Nathan. He signed us, he wanted a two-syllable name, and he said, “I’m gonna call you the Mascots.” And we said, “Okay.”

A little later on you hooked up with Eddie O’Jay.

That’s right. After that record came out that we did in Cincinnati, I guess they shipped it all to different cities, and Eddie O’Jay was on a radio station in Cleveland. He asked us to come to Cleveland to do a sock hop and some other things that he was involved in. Trying to get exposure, we went. He had a good talk with us, because we did that for him several times. And he wanted to manage. But he couldn’t personally do it. So he put it in Audrey’s name, his wife. She was our manager. But he was actually doing the legwork behind the scenes.

So he really was your mentor at that point.

Yeah, he was. He took us to Berry Gordy to get a deal in Detroit. He didn’t like the deal, so we didn’t sign with Berry. But we did sign with Peaches. His wife Thelma. His ex-wife, actually, at the time. Thelma Gordy. She had a deal with, I believe, Decca Records, in New York. It’s been a long time, and I may be getting it wrong. I think she called hers Day-Co Records. But we did sign with her.

And we did some recording (produced by H.B. Barnum). Out of that recording, we did a song called “Ball and Chain.” Everybody else called it “How Does It Feel” (1963). But the real name f the record was “Ball and Chain.” I was listening to the radio in Cleveland, and I heard, “Here’s a new one by The O’Jays,” and it was that song. That’s when I knew they had released it.

How did you feel hearing it for the first time?

Like I instantly became a star. (Laughing) But as we know, that’s not true. We had to get out and work that record. Eddie O’Jay had relationships with different disk jockeys around the country, like in Pittsburgh with Sir Walter Raleigh, in Buffalo, in Philadelphia with George Woods and Jimmy Bishop.

From WDAS and Arctic Records.

Absolutely. Absolutely. WDA-Kickin-S. (Laughing)

Those are legendary guys.

Oh, yeah. George Woods was the man, before Frankie Crocker.

Was Frankie Crocker one of Eddie O’Jay’s business partners?

Now that I don’t know, but when Eddie left Buffalo, WUFO I think it was, he went to LIB in New York. And he hooked up with a lot of people. Frankie was one of them. Rocky G, I think they called him, was another one. They all networked together and would come up with deals with certain artists that really should have had a deal but didn’t have a deal, and certainly not a good deal. So they helped us with that. And we moved around a lot.

When did you guys go to Los Angeles?

I believe…1962. We stayed until ’65, right before the riots got under way. We left there and came back to Cleveland to live. And I’m still here.

And that’s around the time Bill Isles left the group.

Bill Isles left after Los Angeles, because he met a young lady there that he obviously fell in love with. We were out on the road, we were in North Carolina, and she called and told him she was having problems maintaining. Of course he said, “I gotta go take care of Laurel. I’ll be back.” He never came back.

Famous last words. But wait, he later became your touring manager for awhile.

He did. After we got a couple of hits under our belt, and we went back to Los Angeles, we were playing the Greek Theatre. He needed a job. We knew him well, ‘cause he had been in the group forever, before he took off, found a new love. We let him be our tour manager for a couple of years.

Walter, you wrote a bunch of songs before Gamble and Huff hooked up with you. And a lot of these songs were really good ones.

What was the name of it?

Gerry Baxter was a guy who you wrote a couple with.

Yeah, yeah. I think that one was called “It’s Alright.”

Okay, that song right there, “That’s Alright”? That is a phenomenal song.

Thank you! And Eddie and I wrote “Lonely Drifter” (1963) which H.B. Barnum did when we signed with him.

There’s another song Barnum produced for you, called “Peace” (1972) that was…

Ooh yeah! Now that one, I thought was, well, I thought was a hit record. It never got to that status. But we did that in a competition in Mexico. Everybody presented a song, and our song was “Peace.” And it got fantastic reviews in Mexico, we did really great at the concert, but they disqualified us.

What?!

They disqualified us because we did choreography and killed the crowd. (Laughing) They were screaming, “O-A’s!” when we left the stage.

Well, lyrically, that’s a message song that showed where your social conscience was even before Gamble and Huff.

Even before them. And Gamble and Huff knew about “Peace,” too. They had heard about it. At that time, I wasn’t doing any lead singing, to say. Until Allen Toussaint (using the pseudonym “Naomi Neville”) sent a demo called “Lipstick Traces” and the famous Tommy LiPuma, who went on do to George Benson, heard it and liked it.

They sent it to Imperial Records, a subsidiary of Liberty. It was Bob Scapp and a guy named Eddie Ray that ran Imperial Records. They heard it, and Tommy LiPuma liked it for Eddie (Levert). Eddie didn’t like it. He asked me if I could sing it. I sang it, and “Lipstick Traces (On A Cigarette)” went Top 40 (in 1965) with Wink Martindale, Bob Eubanks, Casey Kasem. (Laughing) It happened.

That’s awesome.

It was probably our first Top 40. Then after that we left California because of the riots and came back and got a deal with Bell Records.

When you were on Bell, that’s when George Kerr produced your Back On Top record (in 1968).

George Kerr did “I'll Be Sweeter Tomorrow (Than I Was Today).” Written by the Poindexters. We did a couple of things that the Poindexters wrote. They also did a song called “I Dig Your Act” (the B-side to “I’ll Be Sweeter Tomorrow”). And that was big for us.

”I’ll Be Sweeter Tomorrow” was your biggest hit off that record.

Yeah, it was.

And that’s a great song. But for my money, “That’s Alright” was the album’s masterpiece.

Well, of course! Being that I wrote it, I thought so too! But radio gravitated toward the one that the record company thought was the hit, and they were right, too.

What I don’t understand is, they put “That’s Alright” as the B-side to “Don’t You Know A True Love” and the record did not chart!

No it didn’t. Right.

What was that about? With “Don’t You Know A True Love,” it sounded to me like George Kerr was trying to write a Norman Whitfield song for you guys.

Yeah. Yeah. And that happens. Whoever’s in charge of artists’ repertoire got it wrong. And that’s not the first time. That kind of stuff happens.

If they had just flipped the sides, and “That’s Alright” had been the A-side…

Yup…

…Things might have gone differently and you could have blown up four years earlier.

I think whoever has the best relationship with the big guys at the company, they get heard first. I think that still happens today. And I think that’s what happened to us, certainly what happened to me, that my record didn’t get chosen as the one to be released, ended up on a B-side.

You later produced it for another group, right?

Yeah, but I don’t remember who it was!

The Imperial Wonders. A bunch of young guys coming up.

Oh, okay.

That was on Day Wood Records, in ’71. You and Bobby Massey co-produced it.

Uh-huh. (Laughing)

And that record today? It’s selling for four hundred dollars.

Whaaat?!

People have recognized it’s a masterpiece, years later.

Wow. That’s real special. I gotta do some checking. Because I kinda just let it go after a while, which you should never do. But…I thought it sounded too gospel, and they wouldn’t do anything with it.

You and Eddie later wrote some good songs too. Like “It’s Too Strong,” off the In Philadelphia album.

Well, you know what happened because of that? When we first went to Philly International, and I think we were on the Neptune label, we presented that song to Gamble and Huff, and they didn’t know that I sang lead. I don’t know how they couldn’t have known that, because we had done “Lipstick Traces” (On A Cigarette),” and it was a Top 40 hit. So they should have known that I sang lead but they didn’t give me any lead parts until Eddie and I did “It’s Too Strong.” I think what they heard was the gospel flavor. And they used it. They started writing for both of us after that.

So you’re singing lead on “It’s Too Strong.”

Yes.

That’s a seminal song then, in how things turned out.

I think so. I think that’s when they found out.

Are you guys trading leads on “Peace”?

No, I wasn’t involved! I wasn’t included in that. That was Eddie and William Powell.

How did Gamble and Huff link up with you for In Philadelphia? How did they come into the picture?

We were playing the Apollo with the Intruders. They came up to see them. And when they saw us, they got curious as to who was producing us, and they did the research, and found out all of the people that had produced us in the past. But we were no longer with those people. Contracts had run out.

Our managers at the time owned a nightclub in Cleveland on Euclid Avenue named Leo’s Casino. They booked all of the top acts in the country, and Gamble and Huff saw us at the Apollo, wanted to talk to management. They came to Cleveland, and they sat down with Jules Berger and Leo Frank, and they worked out a deal. And then that’s when we went to Philadelphia and recorded.

And this was for In Philadelphia, on Neptune?

The first records were on Neptune. We did a song called “One Night Affair,” and “There’s Someone (Waiting Back Home),” pertaining to what was going on in Vietnam.

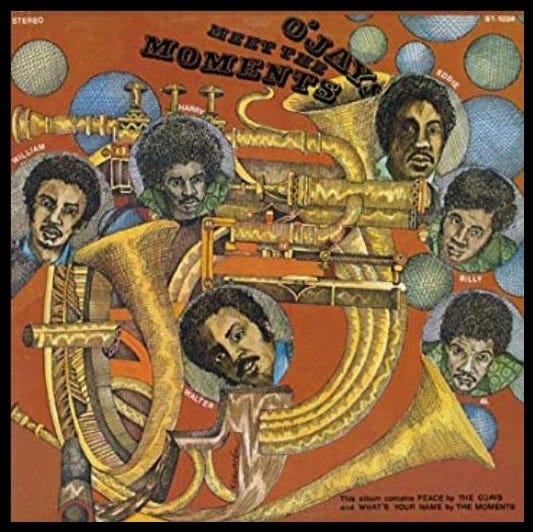

Now, soon afterwards, were you also on Stang for awhile? Or All-Platinum Records?

Wait a minute, say that again? What happened?

Did you also have some stuff out on All-Platinum Records, with Sylvia Robinson? Or were they maybe just distributing some singles?

I think what they started doing was sending out some of the older material that we had done before ever getting with Gamble and Huff. I think they did that on a couple of albums, that they had us in competition with Whispers, Dramatics…

The Moments. The O’Jays meet the Moments (1974).

And the Moments, yeah.

That was one of them.

We had no control of that. Somehow, the record companies got together and put that album together. We had no control. I don’t think I ever got paid for it. (Laughing)

That sucks. Especially because one of the greatest tracks from that album is another song you and Eddie wrote together, called “Feeling Good.”

I remember that one. I sure do. I gotta say, back then, we were not educated enough to have started our own publishing and writing and ways to keep up with what happened with that material. And I’m glad you brought it up, I’m gonna get somebody on it first thing in the morning! (Laughing) Find out what happened with that material, and who claims it right now. Who’s claiming it.

I think “Feeling Good” deserves a whole new generation of listeners. As does “That’s Alright.” People just don’t know these songs, and they should. Because these are some phenomenal tracks.

I agree with you and I appreciate it. You’ve maybe hit on something. We have a guy who’s really good at tracking this kind of stuff down. I’m gonna tell him about it, and maybe he can find something.

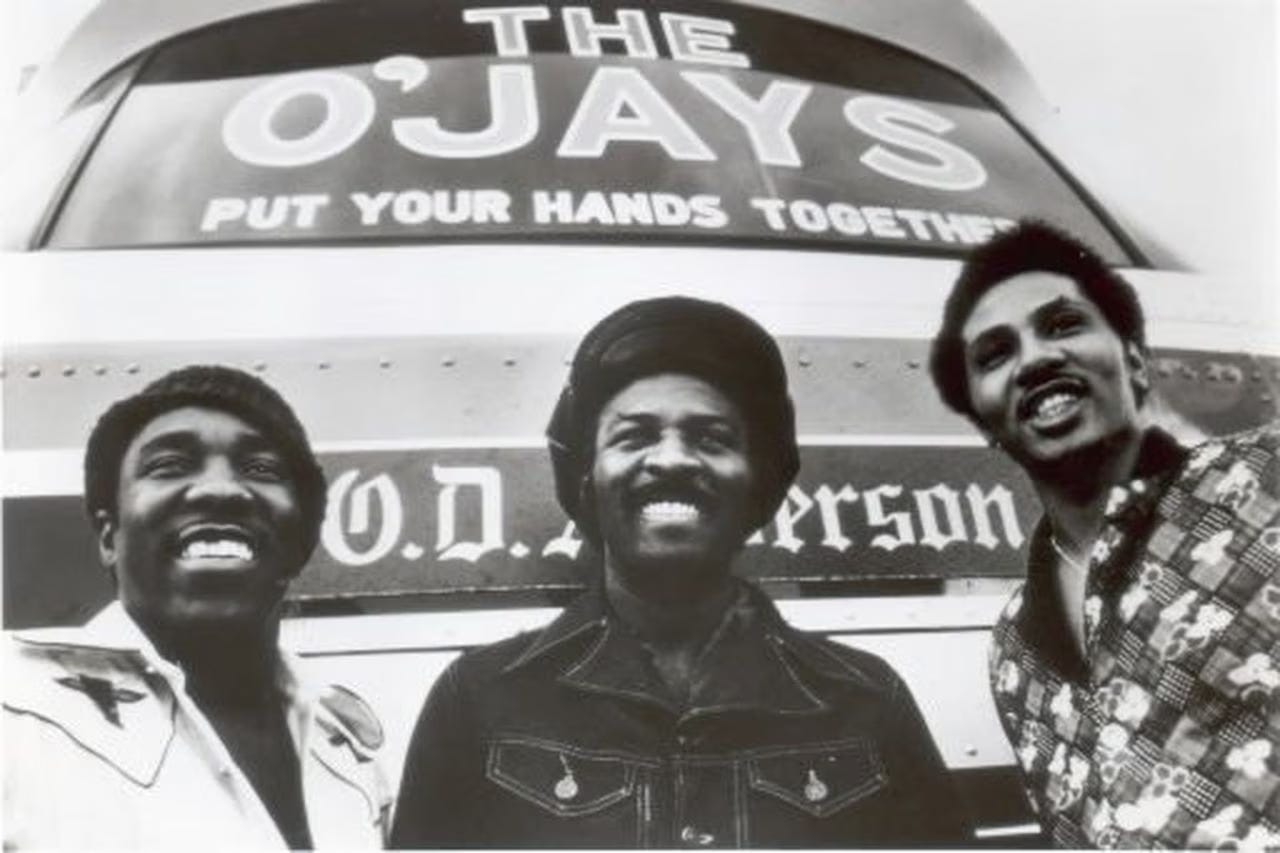

When Bobby Massey left, in 1971, and you guys were (down to) a trio, did you think about calling it a day? Like, ever, at that point?

Absolutely not. I think him leaving the group made the group stronger. And we knew what we had to do then. Because he was the second guy that left. We just knew we had to…we had really put some effort into it, after he left. He, in my opinion, should never have left, totally left the group. He wasn’t the best singer, background or lead-wise, but he was a good businessman. Well, at least I thought he was. Because he did himself a disservice by leaving.

He should have gone into the management area. If nothing more than permanent road manager. He could have done that, and he would have been paid well for doing it. But he was angry because Gamble and Huff would not let him write and produce. I had to fight for that. To get it. And finally, eventually we got it. That we could write, and we could produce. But he left before that, because he was angry they wouldn’t let him do it.

So he knew that you guys were gonna get signed to Philadelphia International.

Yeah.

And he didn’t want to be a part of it if he wasn’t gonna be able to write and produce.

What they told him was, “We’re the writers. We’re the producers.” I’m assuming they had a production contract with CBS when they finally went there. When we got with them, they were with Leonard Chess. And when Leonard Chess passed away, the bottom fell out of everything. And then they went and talked to Walter Yetnikoff and got a deal. And had people like Bruce Lundvall to help. Clive Davis to help.

For CBS to bankroll PIR.

That’s all the help in the world! (Laughing)

And CBS profited handsomely, too. Because they had the next Motown on their hands.

That’s right.

When “Back Stabbers” and “Love Train” both exploded on the charts (in 1972), what went through your mind? What was the first time you realized The O’Jays had made it, and the whole world was gonna know about you?

Well, we knew then we had to catch up and keep up. And I do believe that’s when we hired Cholly Atkins, and we hired a new guy to make uniforms and he was no joke. He really put ‘em on us. And the crowds really loved it.

Your threads were sharp.

Yeah, he did. But later in life like I did, he developed MS. And I think he went all over in France looking for a cure. I went to Cleveland Clinic. No, first I went to UCLA, a good friend of mine, Kitty Sears, took me to UCLA because I was out on the road and it had started to bother me. In ways that I didn’t know what the hell was goin’ on. And so when I got to L.A., she took me to UCLA and I spoke with a doctor Rosner and he diagnosed me with allergic myelitis, otherwise known as multiple sclerosis.

What year was this?

My twins were nine, and they’re forty-nine, so that’s been forty years ago. That must have been in the eighties.

Wow. Well, you would never know it.

Well, I didn’t stop working. My legs were numb, my feet were numb, and doing Cholly Atkins’ choreography was crazy! But I did it. I didn’t want to sit at home because I knew I would not be able to go out there and do what I needed to do if I just sit around. I had a pity party for about maybe two months, and then I got pissed. It was like, “If you gonna get me, you gonna get me fightin’ back. And you gonna be in a fight.” So that’s what I did, I started fighting back.

I started eating better, I started exercising, did a lot of cold walks in the winter because cool makes it feel better. I took cold showers. I read up on it, and tried as best I could to figure out a way to still function with it. It wasn’t until years later I found out about Avonex. Interferon. I got on that shot, and it helped me tremendously. I thank God for that. Seriously, I do. ‘Cause I know without the help and the control that God has in our lives I probably wouldn’t have beat it. But I did! And I’ve been good since!

That’s awesome. You would never know you’ve had any health problems from the way you conduct yourself on stage. You just wouldn’t.

Thank you man, I really appreciate that. (Laughing) It hasn’t been easy, but with the kind of people that’s on my team, and depending on the Good Lord to help out, it’s been easy to go ahead on and do what I need to do.

Praise the Lord that it wasn’t something you couldn’t beat, like with William Powell.

Exactly. He had cancer, and he couldn’t beat it. It got him, eventually.

What was it like when he passed? What was it like losing him?

Oh, wow. It was devastating. Because we grew up together as kids. I met him when I was probably 14, 15 years old. When you really miss them is when you’re traveling, and they’re not in the car, or they’re not on the plane, and you look around, and it’s like, “Damn! Will is gone!” And he’s not coming back. At his funeral, it was difficult. It was in Canton, where everybody knew us, because we grew up there. And I don’t believe they were trying to be (disrespectful), but some came up asking for autographs. And that wasn’t the time.

No.

So things happened that weren’t timely, but we fought through it, and we got through it.

It’s a shame, he died at such a young age. At least he was with you when you made it to the top. And he got to have that experience.

Yes he was.

I cannot think of another R&B group from the 70s who had as much success (as you did) with songs that actually said something, had a social conscience, and were message songs that meant something.

Well, we were blessed to run into Gamble and Huff, and cut a deal with them and go forward. They were excellent writers, they were conscious about what was happening in the world, and we were the messengers! They gave it to us, and we put our thing on it, and then they gave it to the public and the public said whether or not they agreed. With “Love Train,” they REALLY agreed, that’s the biggest one to date, and it still gets the response in the show that it should get. We were blessed to get it.

Gamble and Huff gave you the material, but if you weren’t on the same page, you wouldn’t have sung these songs. You believe in these songs.

Oh, absolutely. It’s the right lyric and it gives the big, bad message. Like love. Love is all throughout the Bible. It was about love, and no one could deny that. And we talked about different countries that agreed. England, China, India, you know. We talked about all these places, and definitely (we all) could use a little more love.

With “Put Your Hands Together,” again, you created an anthem that celebrates equality, freedom, and justice.

Yes. Yes. I think they realized early on that we had that gospel flavor in the way we sing, and the way we build our harmonies, and Joe Tarsia was the best engineer in the world.

At Sigma Sound Studios.

They were solid writers and producers, and my God, they had a team of at least thirty teams of writers. But the ones that were the best for us were Gamble and Huff, McFadden and Whitehead, and Bunny Sigler. Those were the best writers for us that kept us in line (with) the best that we could do. And it worked!

Did you get close to any members of MFSB? Like Norman Harris?

Yes. Norman Harris, the guitarist. The other guitarist, what was his name…

Yeah, Bobby Eli, he was good as well. They used him a lot. The other one I’m trying to think of, they really liked because of his flavor.

Theodore Life, T. Life? He was a guitarist too, but I don’t know if that’s the guy.

No, lemme see…Ronnie Baker was the bass player. He was awesome. But this guitarist was the one they had to have. I mean, he was on everything. Norman Harris was on most of the stuff, but there’s another guy. Karl Chambers?

Oh! Okay, Roland Chambers?

Roland! Yes, Karl was his brother. Roland! (Laughing) Roland played some of the best licks I’ve ever heard. (Laughing) And they loved Roland. So the four main people in the rhythm section were Leon Huff, Roland Chambers, Ronnie Baker, and the drummer.

Earl Young. That was it, man. And that rest of that was gravy. Was cream on top of cherries.

You guys were blessed. You had arguably the greatest R&B producers and writers of the 70s, and the greatest backing band, and three heavenly voices!

Oh, man. Yes, we were blessed. I sat in the studio and sharpened my skills on writing and producing just from being in the studio, watching and learning how Gamble and Huff put songs together and made them happen. I mean, we start off one way, and I would be liking that, and then Gamble or Huff would say, “Naw, let’s not go that way. Let’s try this.” That’s how all of those songs came together, right there in the studio, with them doing their magic to them. Unbelievable.

How did Betty Wright come to produce your final album, The Last Word?

Now, they didn’t have any involvement in that. I wanted them to, but obviously they didn’t work it out at S-Curve.

You wanted Gamble and Huff to produce it.

Yeah, I wanted them to do a couple of things at least. But they chose the writers they wanted. Betty Wright was involved in it. And she was good. And the songs were good. But I think it came down to the mix. We usually had a heavy bottom. Lot of foot, lot of bass, and instruments that played the melody along with us when we sang them. And the guy at S-Curve had different ideas. He brought in different producers, different writers. I think the kid out in Hawaii even gave us a song. What’s his name. Real popular guy.

I’m not sure. All I know is that Betty…

Oh, he’s huge. He’s huge now. He’s old school, and he’s Hawaiian, I think.

I just know Betty and her bandleader Angelo Morris, they co-wrote your best track off that record, by my estimate, “Above The Law.”

He wrote a song on that?

On Last Word, yeah.

I did not know that.

“Enjoy Yourself”? Something like that. Is that a title on there?

Not sure, but I’m gonna find out. That’s cool.

(Laughing) That’s real cool. I wish he had come and sang with us. (Laughing)

Right! (Laughing) What did you think of the song “Above The Law,” the first time you heard it?

I thought it was a great idea. I saw it happening in real life. It’s still happening in real life, with the same people, and I think they blocked it (from) getting airplay. You know, we did a song years ago called “Rich Get Richer,” and we mentioned a couple of families on that particular record, and I think they blocked it as well, ‘cause it got no airplay.

And that takes a big powerful person to stop you from getting airplay on specific songs. Actually, Jesse Jackson did that to us on a song.

Really?

Called “Work On Me.” And he didn’t like it…he said it was too…we said too much negative stuff, he thought it was sexual. It could have been looked at that way, but it could have been looked at a different way, as well.

This was when he was campaigning against supposedly explicit R&B.

Thank you very much. That’s exactly what it was. And that’s exactly the way he put it. (Laughing) We’re friends, actually.

I say “supposedly,” because I’m sure that song was not offensive in the least.

Look, I have love for Jesse. But he didn’t like that song. He didn’t like “Work On Me.” Work me over. (Laughing) And so he didn’t want them to play it, and he said (so).

“Rich Get Richer” was never released as a single, although it should have been.

Yup.

And I feel you 100% as far as the powers-that-be taking whatever steps needed to try to suppress that song and the album it was on.

Yes. And they did. They did that. Because, S-Curve, I was told, put a lot of money behind that album. And it went absolutely nowhere. Not one song off that album is in the show. Well, you just witnessed it.

That’s y’all’s decision. I personally think “Above The Law” would be a theme song that’s even more relevant for what’s happening right now with Trump and his myriad of indictments coming down.

Well, I wasn’t gonna mention him. ‘Cause it only helps (him) when you mention him. (Laughing) But you’re absolutely correct. I think at some point, we might have to put that back in the show, as short-lived as the rest of our career is. But it does make a statement. And I’m sure a lot of people don’t like the statement, especially those (who) follow Trump.

I can’t believe there’s that much overlap between your audience and diehard Trump fans. (But) I know you’ve seen people walk out of your shows at some point over the years.

Yeah. Yeah.

There’s always gonna be some people who are offended by artists saying what’s on their minds.

Well, I saw it happen in Westbury (on Long Island, NY), and I’ve seen it happen in other places that didn’t agree with us if we put Donald Trump down. And it’s okay. They even called the office. They called management. There were threats made, and all that kind of craziness. But the reason we took “Above The Law” out of the show was because it was dead weight. It got no response. And as you can see how our show is built, it’s built for response, you know? That’s when you know that your audience is involved. When they respond to what you’re doing.

If you had to pick one song, Walter, that you would want associated with you, and your overall career…

That would have to be “Love Train.” The message. The way it sold. It sold a couple of million in two or three weeks. So it’s saying the right thing and it’s still big in the show. And of course, it’s our exit song. Which used to be “For The Love Of Money.” When people heard that, they start heading for the exits. Tryin’ to get to the parking lot and get out before the mass rush started. So now it’s “Love Train.”

Do you have another favorite, that’s maybe not as well known?

Oh wow. Let’s see, what would that be…

One that means something to you.

One song that means something to me? I would have to say “For The Love Of Money.” There’s a big message in that one too. It’s an accurate message. (Laughing)

It’s a powerful message, and it’s a shame that it was exploited (with its lyrical content edited out) by Mark Burnett for The Apprentice like it was.

Yeah. Yeah.

I feel like you guys thought that song was gonna be (played) in its entirety and expose people to an anti-greed message.

Exactly. I would have to say it helped us though. Just by that national coverage. Every time it came on. I gotta say it helped us. But they could have done more.

Well, you guys have done plenty over the years to let people know what’s been going on, and the world is better off having had The O’Jays around for as long as you have been. I want to thank you so much for everything you’ve given us.

I appreciate that to the bone. Thank you so much. This was a good interview. I liked it.

Thank you, Walter.

Happy 80th Birthday to the great Walter Williams Sr., and thank you for everything The O’Jays have done to spread the messages of freedom, justice, equality and love through your music.

Further info:

“O'Jays, Gamble & Huff enjoy nostalgic reunion,” by Kimberly C. Roberts, Philadelphia Tribune, June 9, 2015.

“The O’Jays Walter Williams, Sr: An inspiration, legend and man of great wisdom,” by Jessica N. Abraham, NewsBreak, February 11, 2021.

“Story of the song: Back Stabbers by The O’Jays,” by Robert Webb, The Independent, June 24, 2023.

#soul #funk #Philly #PIR #TheOJays #EddieLevert #WalterWilliams

It's great to hear their story from one of the original members.