Rick James (February 1, 1948 – August 6, 2004) – Bustin' Out (On Funk) (1979)

A timeless freedom anthem for folks who don't fit in square boxes, written and produced by the musical genius who blazed his own uncompromising path.

Watch full video on Substack or Twitter.

Rick James was an icon, rebel and musical genius, gone too soon at age 56. His birthday falls on the date the modern civil rights movement was destined to be boosted by the Greensboro sit-ins, and his uncompromising career would have been unimaginable before segregation's overthrow.

James’ rebellious funk masterpiece “Bustin’ Out (On Funk)” (1979) remains a timeless anthem for folks who don’t fit in square boxes, and a striking example of how much our country changed in a relatively short period of time after the walls of segregation were brought tumbling down.

The same day James turned twelve years old in Buffalo, New York on February 1, 1960, four Black students from North Carolina A&T University began the Greensboro lunch counter sit-ins. Their actions inspired similar sit-ins throughout the South, fanning the flames of the civil rights movement.

What a different world it was. Black citizens were prevented from voting in Southern states, which also had Jim Crow laws on their books enforcing racial segregation. They could be murdered, raped, or beaten with near-impunity by white Southerners.

Laws and customs throughout the nation dictated where and how African-Americans could live, work, travel, rest, seek healthcare, and eat or drink. Public schools were separate and unequal, and laws prevented interracial marriage.

In 1959, only 6% of Southern hospitals were integrated, and a third of the rest flat out refused to admit Black patients. Although 70% of white children in Mississippi were born in hospitals, 90% of the state’s Black children were delivered at home, greatly increasing their infant mortality rates.

Even in the absence of segregation laws, Black Americans faced discrimination in hiring, housing, and daily life. Black travelers had to rely on an annually published travel guide called The Green Book that listed hotels, motels and restaurants where they wouldn’t be turned away. Major publishers seldom released books about African-Americans, and they were relegated to small roles on film, radio and television or portrayed as negative stereotypes.

But as the twentieth century progressed, the growing popularity of jazz and R&B helped break down some of segregation’s barriers. The music had an appeal across color lines that allowed it to function as the “universal language” the great producer Van McCoy and others envisioned. Eventually, Black artists provided the soundtrack to the civil rights movement.

Berry Gordy’s Tamla record label was barely a year old on February 1, 1960, still two months away from being incorporated as Motown Record Corporation. Their first real hit, “Money (That’s What I Want)” by Barrett Strong, wouldn’t become a success until that June. The label’s first million-seller, The Miracles’ “Shop Around,” was seven months away from being released in September, 1960.

Nineteen years later in 1979, legal segregation was dead and buried. Motown was an institution, and Black artists ruled the charts at the height of the disco era.

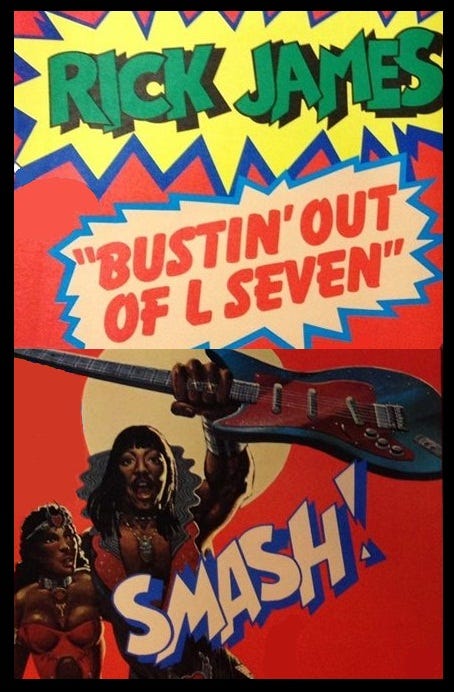

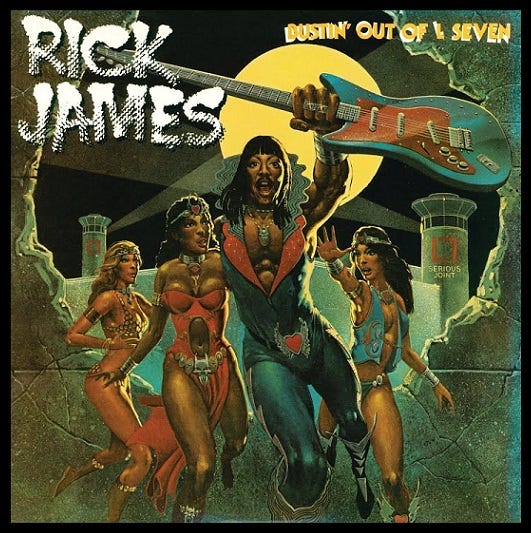

The Motown sub-label Gordy released James’ second solo album Bustin’ Out Of L Seven on January 26, 1979, five days short of his 31st birthday.

It sold over a million copies, hitting #2 on the R&B albums chart, and #16 on the Billboard 200.

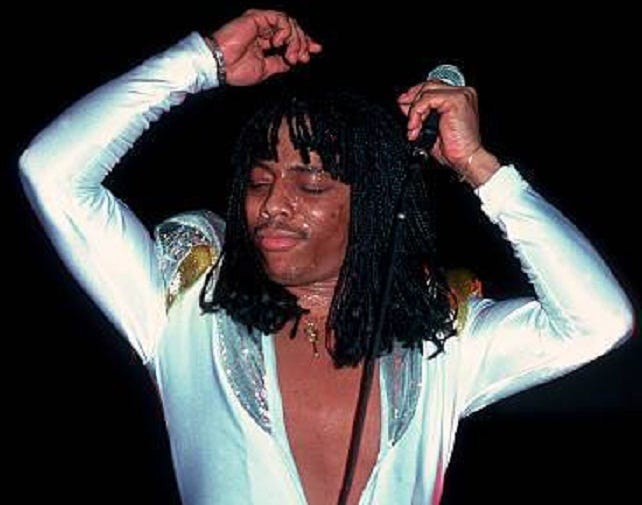

Rick James in Buffalo, NY, 1977

This followed up on the previous year’s success of his debut LP Come Get It! (1978), which eventually sold two million, juicing Motown’s sales at a difficult time for the company. By the mid-70s, top producers like Holland-Dozier-Holland, Norman Whitfield, the Mizell Brothers, and Freddie Perren had all departed.

The title track to Bustin’ Out Of L Seven, James’ defiant funk anthem “Bustin' Out (On Funk)” was released as a single, and made it to #8 R&B. It didn’t cross over to white audiences, only reaching #71 on the Billboard Hot 100. In this case, the universal language was a little too funky.

Along with Stone City Band members Oscar Alston on bass, Levi Ruffin, Jr. and Clarence Sims on synthesizers/keyboards, plus Lanise Hughes on drums, it featured Michael and Randy Brecker on horns, and James’ protégé Teena Marie on background vocals.

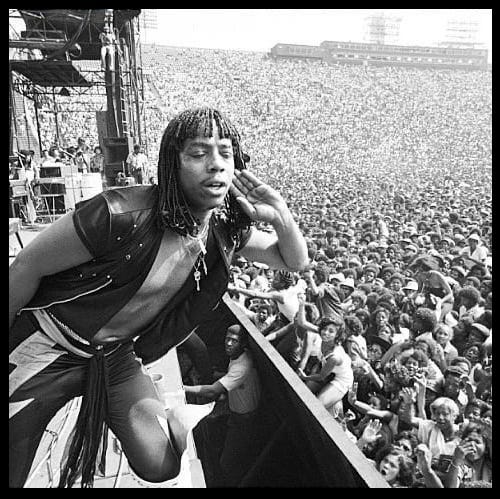

Lyrically, it spoke to funky misfits and refugees from square society everywhere, letting the world know, “We don't give a damn, if you don't like our funk, you can take your stuff and scram!”

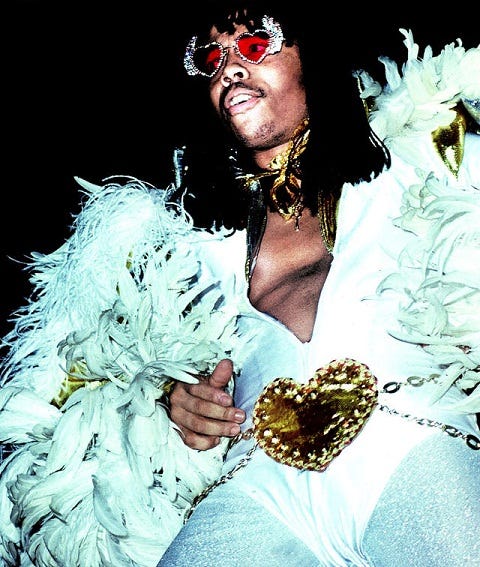

Like many of Rick James' greatest songs, nearly all of which he wrote and produced himself, “Bustin' Out (On Funk)” is a freedom anthem. Not just the freedom to be Black in America, or funky, but to be Black, funky, and freaky.

Rick James was a superstar by the end of the 70s. He was able to celebrate his funkiness, sexuality and drug use in a way inconceivable for Black artists two decades earlier, while being justly recognized by the record buying public for his musical genius.

#funk #soul #civilrightsmovement #BlackHistoryMonth #Motown #RickJames

Outstanding. 🎼👊🏾