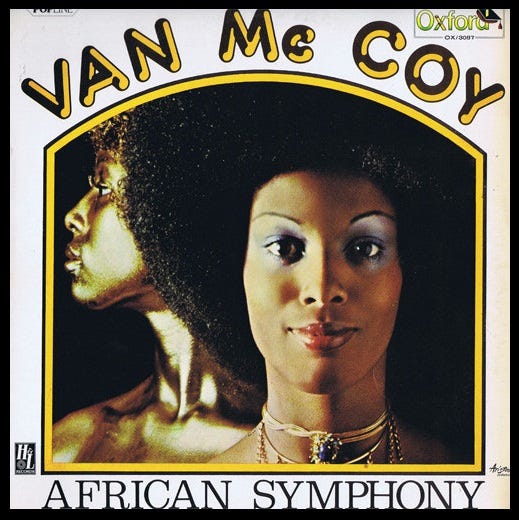

Van McCoy (January 6, 1940 – July 6, 1979) - African Symphony (1974)

An epic, cinematic, instrumental masterpiece from the music legend who wrote 700 songs during his career as producer, arranger, conductor, and singer/songwriter.

Watch full video on Substack or Twitter.

The supremely talented producer, arranger, conductor, singer/songwriter, and recording artist Van McCoy (January 6, 1940 – July 6, 1979) turbo charged disco’s popularity with his hit “The Hustle.” He wrote approximately 700 songs during his prolific two decades in the music industry.

Van Allen Clinton McCoy was born in Washington, D.C. He learned to play piano as a young boy and began writing his own songs by age 12. In high school he formed a doo-wop group called the Starlighters. He spent two years at Howard University starting in 1958 but dropped out to focus on producing music.

McCoy moved to Philadelpia where he started his first record company, Rockin’ Records. Its initial release in 1959 was the doo-wop ballad “Hey Mr. DJ,” a song he wrote, sang, and released under his own name. The single was a modest success, reaching #104 on the pop charts, and resulted in McCoy being hired by Scepter Records as a staff writer and A&R rep.

During the sixties, McCoy worked with producers Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller, then signed with the April-Blackwood music publishing company which was connected to Columbia Records. He wrote and produced songs for numerous other artists.

McCoy wrote “Giving Up” for Gladys Knight & The Pips in 1964, which became their third top-40 single (#38 pop) and peaked at #6 on the Billboard R&B charts. It was largely due to this record’s impact that the band was signed to Motown two years later.

Other songs he wrote during this period included Betty Everett’s “Getting Mighty Crowded” (1964), an upbeat dancefloor filler that became an early Northern Soul favorite; “I Get The Sweetest Feeling” (1968) for Jackie Wilson, backed by the Funk Brothers, which became a top-ten hit in the UK twice when it was re-released there in 1972 and 1987; and the Barbara Lewis classic “Baby I’m Yours” (1965). It went to #1 in the Detroit market in 1965 and ended up at #11 on the national pop charts and #5 R&B.

He put together the group Peaches & Herb after discovering singer Herb Fame working at a D.C. record store, and co-produced and arranged their first hit “Let’s Fall In Love” (1966).

In the early 70s, he began collaborating with fellow songwriter/producer Charles Kipps. McCoy released his first solo LP in 1972 on Buddah Records, Soul Improvisations, which bombed due to poor promotion. He produced several albums in the early to mid-70s for the trio Faith, Hope and Charity, featuring singer Zulema Cusseaux. After Thom Bell stopped working with the Stylistics, McCoy arranged and conducted their next two albums, Heavy and Let’s Put It All Together, both released in 1974.

McCoy put together his own orchestra, the Soul City Symphony, and in 1974 they backed him on his Love Is The Answer LP. The album’s masterpiece was the epic, cinematic instrumental “African Symphony.”

He arranged and conducted the entire album. However, “African Symphony” was one of only two songs McCoy wrote for this LP, the other being its funky, appropriately named closing cut “Funky Feet.” Love Is The Answer was produced by Hugo & Luigi, aka Hugo Peretti and Luigi Creatore, two cousins and Brill Building songwriters/producers who bought Avco Records in the late sixties and eventually renamed it H&L Records.

“African Symphony” was later updated for disco dancefloors as “La Symphonie Africaine” (1977), a cover version by Saint Tropez, one of the many disco studio projects of producers Laurin Rinder and W. Michael Lewis.

In 1975, McCoy released his second album with the Soul City Symphony, Disco Baby. Filled mostly with instrumentals, the last track to be recorded was one McCoy wrote after going with his music partner Charles Kipps to see dancers perform a dance called the Hustle at the Adam’s Apple disco in New York City.

Watch full video on Substack or Twitter.

Released as a single that April, “The Hustle” topped both the pop and R&B charts, was an international smash hit, and won McCoy a Grammy for Best Pop Instrumental Performance of 1975. Its success arguably did more to popularize disco in the 70s than any other single song.

In a fascinating column McCoy wrote in March, 1979 only a few months before his death, he described how the rise of disco meant "white and black musical styles are merging and creating a new sound," a universal language of music that could bring us all together. “Disco breaks down the barriers between people,” he noted. “It’s the music and the beat that matters.”

View larger version on Substack or Twitter.

Van McCoy died in Englewood, New Jersey on July 6, 1979 of a heart attack. He was only 39 years old. McCoy did not live to see the racist, homophobic anti-disco backlash that closed out the seventies and delayed his vision of eventual racial unity through music, which got its symbolic kickoff less than a week after his death. On July 12, 1979 the infamous Disco Demolition Night at a Chicago White Sox game ended in a racist riot as the mostly white male crowd destroyed records by Black artists.

But disco didn’t die that night, or because of the backlash. It went back underground, then re-emerged as house music in the 1980s which grew into the thriving global electronic dance music community that exists today. Disco will live on forever, and Van McCoy helped make it happen.

#soul #funk #disco #VanMcCoy