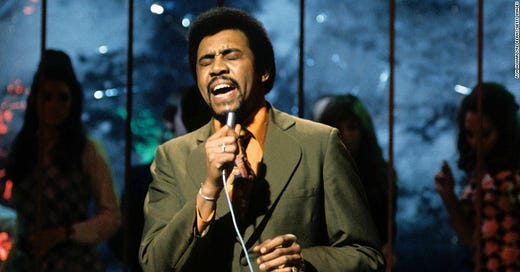

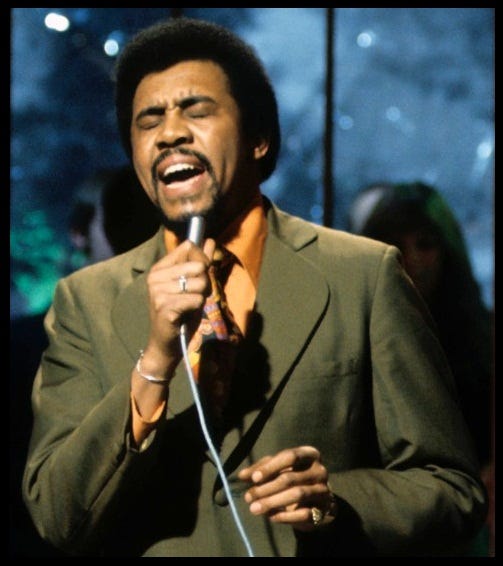

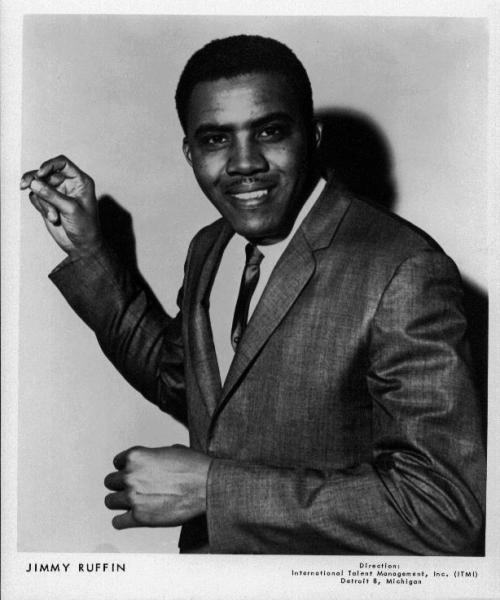

Jimmy Ruffin (May 7, 1936 – November 17, 2014) – Tears Of Joy (1973)

Destined to be overshadowed by his younger brother David, the Motown singer's talent still burned bright on songs he wrote like this soul masterpiece.

Watch full video on YouTube.

View most updated version of this post on Substack.

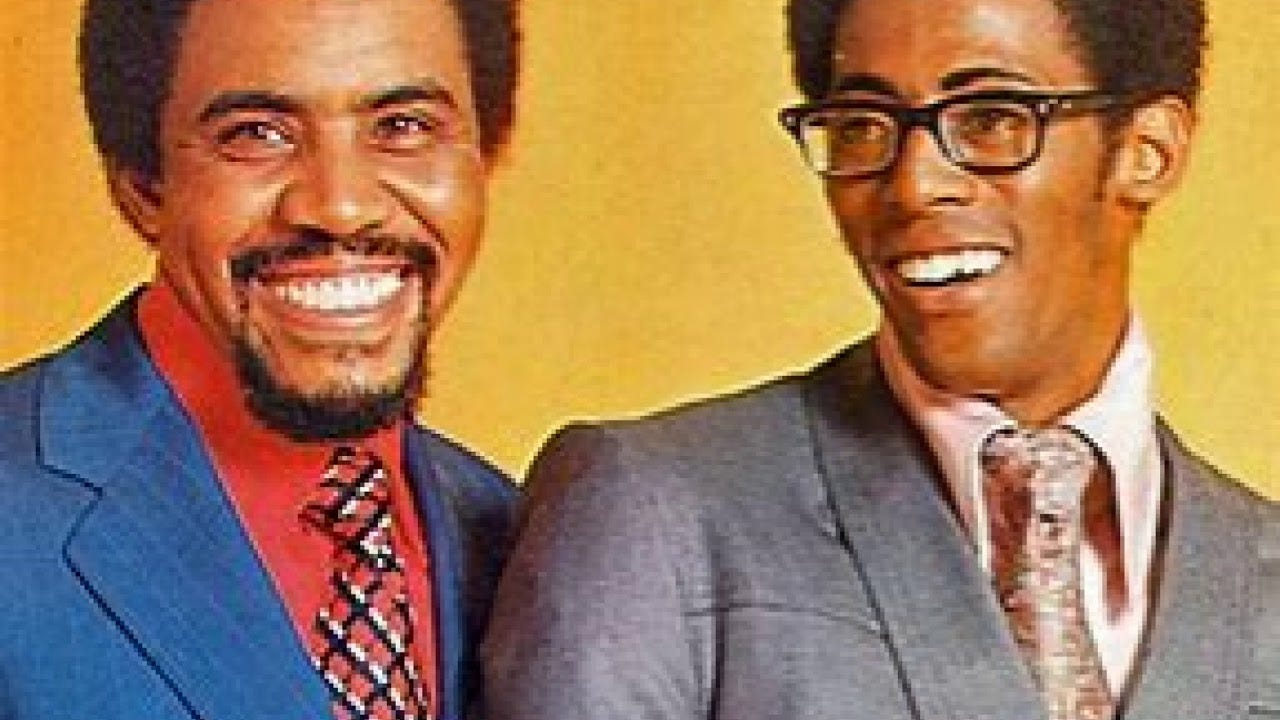

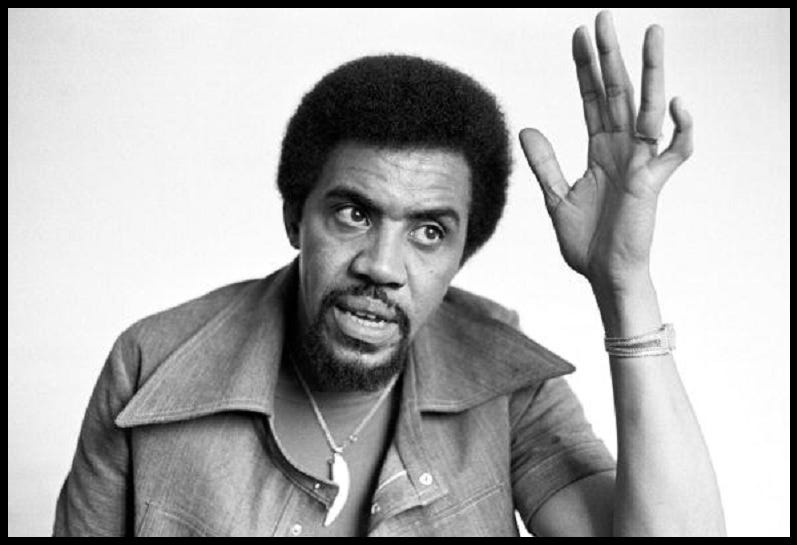

Jimmy Ruffin was a talented Motown singer/songwriter best known for his 1966 classic “What Becomes of the Brokenhearted.” He was the older brother of Temptations lead singer David Ruffin.

Ruffin was born in Mississippi, the son of a sharecropper. His younger brother David came along five years later. The brothers sang with their family’s gospel group and later both joined the Dixie Nightingales, a male vocal gospel group.

Jimmy moved to Detroit, where in 1961 he began working with Berry Gordy’s fledging Motown operation. He sang backup for recording sessions and also released his debut single that same year, “Don't Feel Sorry for Me” b/w “Heart” on the label’s Miracle Records subsidiary. Ruffin wrote both songs himself, which were produced by “Miss Ray,” aka Raynoma Mayberry Liles Gordy, who was Gordy’s wife at the time.

David followed his brother to Detroit, where he released several singles of his own that did not chart. In 1963, Jimmy and David both auditioned to replace original Temptations member Al Bryant. Most sources state Jimmy was offered the job at first, but they eventually chose David, and Jimmy continued recording as a solo artist. Years later, however, Jimmy claimed there was more to the story:

“The second [best decision of my life] was NOT joining The Temptations. They were begging me to join but I wanted to be solo - I'd been used to having my own group, I didn't want to have another one. So then I spent time persuading my brother David that he should join them instead.”

See our earlier post on David Ruffin for more on the brothers’ musical careers at Motown.

In 1965, Jimmy put out his third single, “As Long as There Is L-O-V-E Love,” which became a hit in Detroit and his first entry on Billboard’s national charts at #120. Its follow-up was a song originally written for the Spinners, but after hearing it, he convinced its writers (William Weatherspoon, James Dean, and trombonist and Funk Brother Paul Riser) to let him cut it instead. “What Becomes of the Brokenhearted” was recorded in February, 1966, backed by the Funk Brothers with joint backing vocals from both the Originals and the Andantes, produced by Weatherspoon and William “Mickey” Stevenson.

Released that June, it was Ruffin’s biggest-ever hit, reaching #6 R&B, #7 on the Billboard Hot 100, and #8 on the UK singles chart. Its success led Motown to release his first full-length album Jimmy Ruffin Sings Top Ten in January, 1967. Another three of his LP’s (including one with David) and at least fifteen singles were issued on Motown-affiliated labels over the next several years. In a 1999 interview, Ruffin reflected on how he dealt with his new-found fame:

“The pressure is incredible. A lot of people died from the pressure, including my brother David. Suddenly you're moving up in society, going to places you're not really prepared for - beyond your own race, culture and class, your own country. I was pretty well grounded, I'd got a philosophy of life from my grandmother. I'm an observer not a joiner, so I didn't participate in the drugs except in a minor way - I don't like being out of my mind. So I survived. I may not have had as much celebrity as people like Marvin [Gaye] but I'm still here.”

He performed alongside the Supremes and Temptations on some of the label’s Motown Revue package concert tours in the mid-sixties, but according to Ruffin, “the problem there was that I was too good. They were headlining but I got the standing ovations - so they took me off the tour.”

Unfortunately, his records faded from the U.S. charts fairly quickly. For one thing, his name was overshadowed by that of his more famous brother, who launched his own solo career after being fired by the Temptations in 1968. Many of Jimmy’s songs were also covered by other Motown artists who rode them to greater success. However, in the UK the growing taste for Northern Soul saw him score three top-ten hits during 1969-70. In 1970, Ruffin moved to London to capitalize on his popularity there, and lived in the UK for the next two decades.

One of Ruffin’s stellar but less known tracks from this era was the upbeat but poignant love song “On the Way Out (On the Way In).” It was co-written by Dean and Weatherspoon, and included on his album The Groove Governor, released in 1970 on Motown’s Soul Records imprint. Released as a single in the UK only, it still failed to chart.

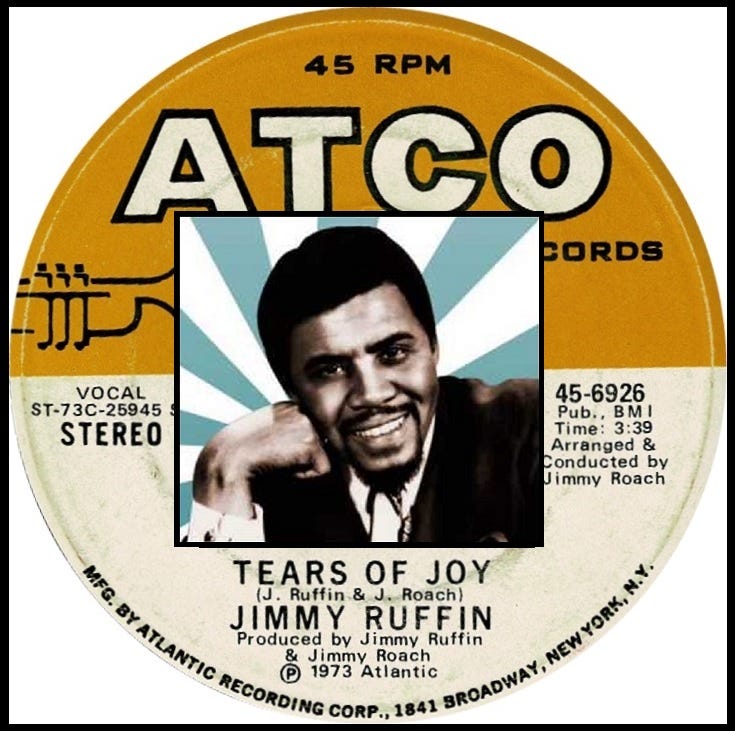

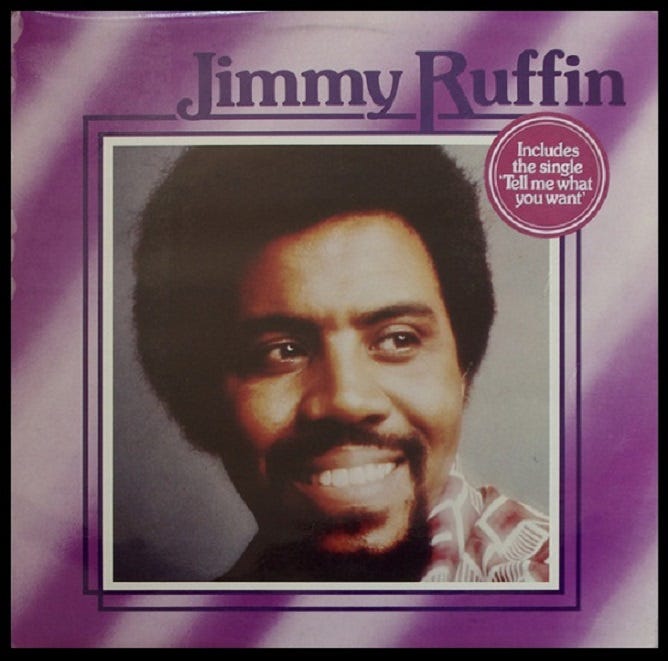

Jimmy left Motown in 1972. His self-titled 1973 LP for Polydor was only released in the UK, despite having been recorded in Detroit and Philadelphia. The album’s masterpiece was arguably the beautiful song “Tears of Joy,” which Ruffin co-wrote and produced with Jimmy Roach and played guitar on.

Like most of the album, it was backed by Funk Brothers Robert White, Eddie Willis, and Dennis Coffey on guitars, Bob Babbitt on bass, keyboardist Joe Hunter, Johnny Griffith on piano, Eddie “Bongo” Brown on bongos, and drummer Andrew Smith. Released as the B-side of the stellar non-LP track “Goin’ Home” on Atco Records in the U.S., it still failed to chart.

Four of its cuts were recorded at Sigma Sound Studios in Philly, including the superb soul/disco jam “Tell Me What You Want” which he wrote. They featured many members of Philadelphia International Records’ house band MFSB including core original members Ronnie Baker, Norman Harris, Earl Young and Bobby Eli. “Tell Me What You Want” returned him to the U.S. charts when it hit #42 R&B.

Other highlights that Ruffin wrote for the LP were the autobiographical “Boy From Mississippi,” and the powerful message song “Super Brother.”

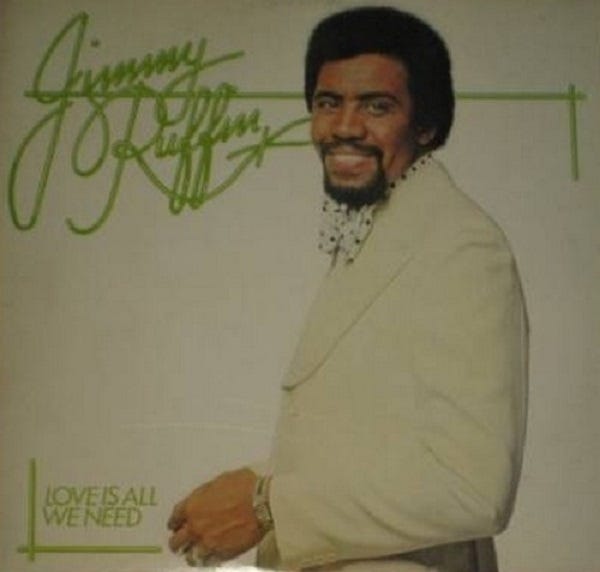

In 1975, Polydor released Love Is All We Need, Ruffin’s second and final album for the label. It was again issued only in the UK, and again failed to chart.

The LP paired him with some of the finest soul and funk musicians who were then working in Detroit, Philadelphia, and Los Angeles. Ruffin wrote and produced the powerful self-empowerment anthem “Get On Up,” which was again recorded at Sigma Sound and featured Norman Harris and Bobby Eli on guitars, bassist Jimmy DeJulio, drummer Ronald Di Stefano, Larry Washington on congas, and Richie Rome on keyboards, who also arranged it.

Ruffin also wrote the upbeat funk anthem “Layin’ It Down,” which he co-produced with Jimmy Roach and played guitar on. It was recorded at Pampa Studios in Detroit, which was located in the basement of a bowling alley. Funk Brothers backing him included Robert White, Eddie Willis and Dennis Coffey on guitars, Joe Hunter on keyboards, Bob Babbitt on bass, Eddie “Bongo” Brown on bongos, and Kenny “Spider Webb” Rice on drums. The track was inexplicably never released as a single, but he memorably performed it live on an episode of the Swiss music TV show Hits à gogo in 1973.

After returning to the United States, Ruffin lived in Las Vegas during the last years of his life. At the time of his death at age 78, he was working on one final album that remains unreleased.

Rest in Power, Jimmy Ruffin.

Further info:

“Jimmy Ruffin,” interview, BBC, June 8, 1999.

“How Jimmy Ruffin made Motown's best-ever single,” The Guardian, November 19, 2014.

“Jimmy Ruffin, Singer of a Memorable Motown Hit, Dies at 78,” obituary, The New York Times, November 20, 2014.

#soul #funk #Motown #JimmyRuffin

I think I mentioned the night in 1967 when some high school friends and I went to the Howard Theater in D.C. to see The Temptations. There were two acts and a standup comedy interlude by the masterful Jimmy Pelham before The Temptations appeared. Jimmy Ruffin was the second musical act of the night -- the first was a Motown girl group my friends and I had never heard before -- and he didn’t disappoint. It was a short set, though; and right after singing the magnificent “Brokenhearted,” which was a huge favorite among my friends and me, there was a delay by the band as they struggled to get their shit together for the next song.

Ruffin seemed a little troubled by the delay, glancing toward the band for some indication that there would be an end to the disturbance; so he faced the audience again with composure and just started to speak in what my friends and I later called “soul quotes.”

“Brokenhearted” and other soul favorites of ours at the time were mined by myself and my buddies for “soul quotes” -- fragments of songs that we’d use in everyday conversations.

“Hey, how’d you do on that test?”

“Not good. All that’s left is an unhappy ending. You?”

“I’ve been singin' that sad, sad song.”

You get the idea. Anyway, an endless array of spontaneous soul quotes were fucking pouring out of Ruffin's mouth for about twenty seconds. My friends and I were dying! And none of us later remembered anything he said.